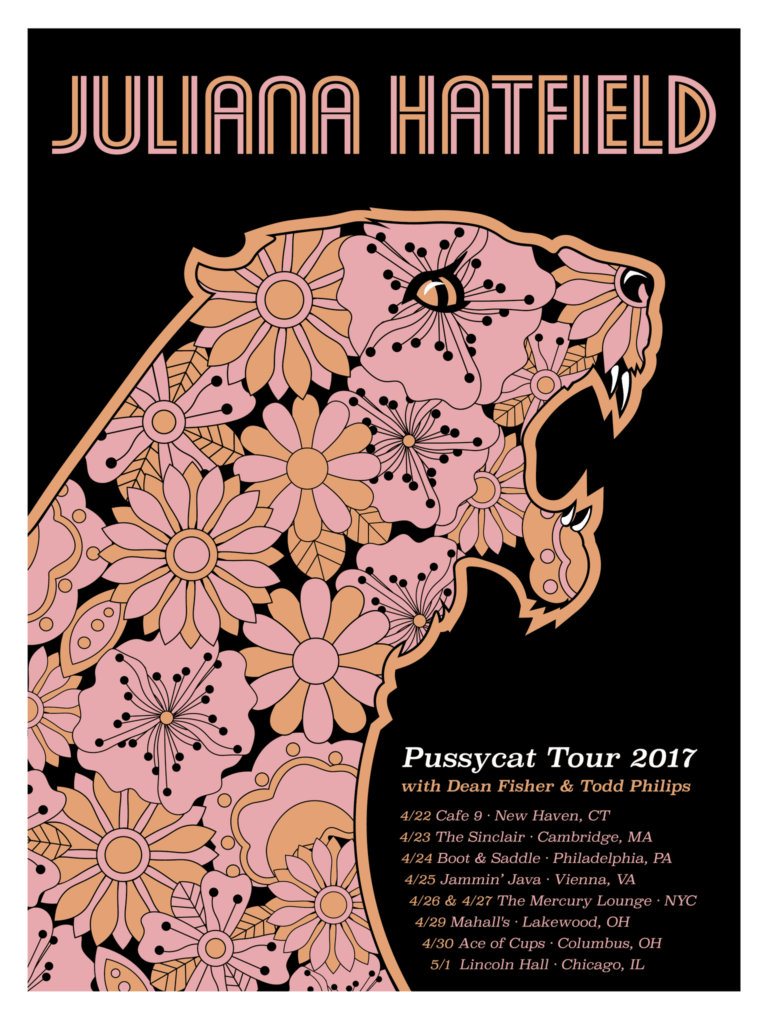

On April 28th, American Laundromat Records will release Pussycat, Juliana Hatfield’s fifteenth studio album. Hatfield says she experienced a productive variety of rage in response to last year’s presidential race and the deeply troubling sociopolitical climate it was both born of and perniciously sustaining. But while the politics and the language of rage may be pronounced on Pussycat, to label it as an “anti-Trump album” is to be reductive on two accounts. First, it appeared quite obvious to this listener that the record is not so much a response to Donald Trump as it is a channeling of the long-held, easily-accessed, unassuageable fury one feels in the dominant culture of sexism, abuse, lookism, and degradation which Trump—though it of course predates him—has come to represent, perpetuate, minimize, sanitize, and reinforce. The fourteen songs that comprise Pussycat are not arguing for the newness or the arrival of anything; they are phoenixes rising from the known and familiar fire of what it is to live in a recursive, crushing, enduring patriarchy. Which brings me to my second point: to classify Pussycat as “anti-Trump” or even to characterize it less generally as “a political album” is to imply, however tacitly, that such subject matter is somehow new terrain for Hatfield, whereas any student of the music she’s put out into the world in the thirty years she’s been a performer will tell you: she’s never been anything but political. I had the great fortune to talk about all of this and more with Juliana via phone last week as she readies for an eight-city tour—accompanied by Dean Fisher and Todd Philips, the brilliant band for her seminal Become What You Are record—to promote Pussycat’s release. (See full list of tour dates after the conversation.)

——— ——— ——— ——— ——— ——— ——— ——— ——— ———

Vincent Scarpa: In the press release for Pussycat, you say you hadn’t been planning on making a record, but that, post-election, “all of these songs started pouring out” and you felt “an urgency to record them, to get them down, and get them out there.” I wonder: are you consciously aware of what activated the impulses toward these songs—that is to say, what opened up in you that allowed them to pour out?

Juliana Hatfield: What happened to me was the same thing that happened to a little more than half of the population, where everyone was energized to do something to counteract the horror of what had just gone down in the election. Also, I must say: a big motivator was the leaked pussy-grab tape. That really, really struck me deep down, as it did millions and millions of women. It really did something to me. It awakened a lot of memories that I’d pushed aside and reminded me of how much shit we’re made to take from other people. The sexism isn’t new—I can remember feeling it back when I was a little girl. But when one of the most powerful men in the whole country was heard to be saying things so crass and so disgusting? I was so angry. I wrote a piece for The Talkhouse about how it affected me.

VS: I thought that essay was excellent.

JH: Thank you for saying that. It’s just crazy-making, the whole thing. The guy has shown himself to be an awful person in so many ways, and it hasn’t affected him at all. There have been no consequences. And now people who are full of hatred feel emboldened by him to express that hatred willy-nilly.

So, to make a long answer really short: that tape really was just a knife in my soul and it activated all these things in me: anger, outrage, hurt. When that happens, the writing happens. Because I can’t write about things I don’t care about; I can’t write when I’m not feeling. I think when I have something I really need to say, it’s easier for me to write, and before this election I hadn’t really been feeling that need. And then suddenly I was in a place where I felt like I had a whole lot I needed to get out of my system, and I did.

VS: When I listen to it, what I hear, over the course of these fourteen songs, is a person trying to comprehend and reconcile the array of reactions and responses to the sociopolitical milieu this past election has ushered the country into. Some of those reactions share some overlap, and some are diametrically opposed to one another, but what the record seems to stress is that none of these reactions are dominant—they’re fluid, they flicker, they flare up and recede. And that feels extremely honest.

JH: Exactly. The record is a document of me trying to navigate the current climate. Like, for example, that song, “Kellyanne.” Yes, it’s called “Kellyanne,” but it’s really about me; about my reaction to her and how I feel when I see her face on TV. What is this dark power that a stranger has over me, and why? That’s part of what’s so scary about this climate: the fury and rage and confusion that these people are stirring up.

VS: I call people like her cultural criminals. People who are just straight-up for sale, with no moral compass whatsoever.

JH: I love that.

VS: And I guess the inverse of songs like “Kellyanne” and “When You’re A Star” is “Impossible Song.” Well, not necessarily the inverse, but there’s an inverted mood and mode that “Impossible Song” seems to come from. In it, you sing, “These contentious times bring out the very worst in me/I don’t like what I’m becoming/What if we tried to get along?/Sing an impossible song?” There’s a measure of hope there, but it really does feel like a question—what if we tried to get along?—rather than a didactic or moralistic, up-with-people command.

JH: For me, that song is a fantasy. It seems like we’re never going to get along. There’s this huge divide. I was just trying to deal with my own rage. It’s not healthy, it’s not productive, and it’s not solving anything. Anger can be a good motivating energy if you know how to harness it, but this rage has been so wild and venomous that I can’t control it. I just explode. I mean, it hasn’t happened publicly, thankfully, and I’ve never unleashed physically on another person or anything, but it’s scary all the same. And it’s not a productive force; it’s destructive. And it’s confusing. And it doesn’t feel good. What do I do with it? How can I calm my reactions? How can I deal with this? How can I deal with the people I don’t agree with and who don’t agree with me?

I was in the bookstore the other day looking at George W. Bush’s book of paintings—the paintings he’s done of veterans—and this older woman came up to me and said, “Isn’t that great? His paintings are so wonderful.” And I was thinking, “These paintings are awful.” I got the sense that she was a fan of his presidency, but we were still able to have this nice little interaction without getting into politics. I have to believe that there’s a possibility for moments between two people who disagree to put aside their rage and their beliefs and their politics and just coexist. We have to, otherwise we’re going to kill each other.

And in that song I wanted to stress, too, that we do have a common humanity, and at some point in our lives we’re all going to have to rely on a stranger, and be relied on by a stranger, and hopefully that stranger’s politics aren’t going to interfere with a genuine need for help.

VS: That’s exactly why I love the song, because it’s drawing a circle around the fact that need does not discriminate or account for one’s politics. Need is nonpartisan. And we’re at this weird cultural moment wherein there’s such a strong embrace and fetishization of laboriousness—like, watch this viral video about an eighteen-year-old who worked four jobs and slept in a storage shed in order to pay a semester’s worth of tuition at a state university! And I’m not saying there isn’t something laudable about that, because of course there is, but when I see stories like that, what seems more pressing and more important isn’t the where-there’s-a-will-there’s-a-way ethos but the fact that, you know, the situation was such that it required this eighteen-year-old to work four jobs and live in a storage shed in the first place. And this bootstraps mentality implies that need is ugly, that dependency is ugly. Whereas I feel like I’m just getting to the point in my own life—maybe the election had something to do with it, I don’t know—but I’m getting to a point where I’m starting to see that there’s beauty in dependency. This poet I love, Eileen Myles, has a poem where she says, “Need each other as much as you can bear, everywhere you go in this world.” And I think in some ways that’s what “Impossible Song” is putting forth, too. That, and it’s also refusing to only be furious. It’s acknowledging how rudderless fury is if you aren’t doing something with it.

JH: Fury isn’t good for you, physically or mentally. It isn’t good for me. So, with “Impossible Song,” it’s just me trying. Trying to chill out. Trying to be more reasonable.

It’s interesting what you’re saying about need, too. I don’t want to depend on anyone, and I’ve always been very independent and self-sufficient. I pride myself on that. But I also know—and maybe because I’m so independent and alone a lot of the time—that there might come a time when I’m actually going to need a stranger. So, I guess that’s something else I’m working to understand in that song, too.

VS: It’s interesting to see some of the buzz building around the record specifying it as “politically-themed”—

JH: It’s annoying.

VS: I can imagine. It’s certainly reductive. But more than anything it just seems like such a strange thing to say, because your music has always felt political to me. I mean, I know that for a lot of people “political” has a narrower definition, and it’s true that that kind of “political” is certainly more conspicuous in some of the songs on Pussycat.

JH: Right.

VS: But coming from a background of critical theory and gender studies, I’ve always believed that the personal is of course political. I mean, I wrote my undergraduate honors thesis on that very subject. I was twenty, so I’m sure I’d be quite mortified to read it now. I don’t even know if I still have it. But I know it had a very pretentious title, something like, “The Confessing Animal: The Politics of the Personal and the Reclamation of Rage for Women in Music.” I was using Foucault’s writing about confession—which I’m sure I didn’t have a complete understanding of then, and probably still don’t—as a kind of lens to look at the music of the women I’d grown up loving and listening to: Fiona Apple, Tori Amos, PJ Harvey—and you! In my section about you, “Feed Me” and “Rats in the Attic” were the two songs I focused on the most. My distillatory understanding of Foucault’s theorizing—which, again, I could still have wrong—was that if the confessional is linked to our understanding of the workings of power, and if confession is essentially the production of truth, then when we produce that truth willingly—not by coercion or threat—we are both speaking to power and making power. So that, in a song like “Rats in the Attic,” say, the speaker who sings “this land is mine” is also the speaker who “can’t fight what grows inside her” and who howls “I got murderous urges”—she’s creating power by virtue of revelation. And what’s more political than that? I’m getting tangential and rhapsodic when what I’m driving at is rather simple, which is whether or not you conceived of this record as making more of a political statement than your previous work had.

JH: I’d love to read that thesis.

VS: God no, I’d be so horrified.

JH: Well, I like what you’re saying there and I think you’re right. But even aside from the confessional, I’ve had straight-up protest songs on previous records that no one talks about. And I guess I’m partially at fault for how [Pussycat] is being written about, because of the bio I put out that said, you know, I wasn’t writing songs and then the election happened and I was writing again. But that somehow became, “Juliana Hatfield writes an anti-Trump album.” And that is not the narrative I want out there. So, I’m trying to take control of that narrative as best as I can, because it really isn’t an Anti-Trump album. It’s Pro-America. It’s Anti-Hatred. And actually, listening to the album recently, I thought: this is more of an anti-sexism, anti-emotional abuse record than anything else. It’s as much Anti-Cosby as Anti-Trump. At this point, Trump is just a symbol of something else, anyway. And the record is about that something else, not him.

VS: You produced Pussycat and played every instrument other than drums. It’s not the first time you’ve done that, right?

JH: It’s not the first, no. Wild Animals and Peace and Love I made that way, but they were more acoustic-y. Whereas playing all the bass and all the guitars on this one was, I guess, novel for me.

VS: Was there something about these songs, this project, that led you to make that decision? Did it feel necessary in some way to be in control in any and all ways possible?

JH: Partly it was just the urgency of the songs, the urgency of how I was feeling at the time. I wanted the songs to feel urgent and timely by the time the record was done. I thought, “Kellyanne might be fired soon!” [Laughs.] And if I do everything, I don’t have to negotiate with anyone about what I like or what I don’t like. I had a very strong, clear vision. And I’d just done some gigs with The Blake Babies playing bass, so I was feeling like my bass chops were kind of lubed up. It was quick, it was economical. Twelve days, recorded and mixed. And I’m so happy with the sound of it. With some of my older records, when I go back and listen to them, I’m disappointed in the sound. But I feel like I finally nailed it on this one. I was very particular. I was very clear with the engineer about exactly what I wanted. And I think cutting out a lot of people in the studio made me more able to have confidence in my vision. When there are other people around, I tend to listen to their opinions. Which isn’t to say their opinions aren’t great—they often are—but I think your vision can be muddied or diffused by other people. Being in there by myself, I was able to really tune in very closely to the process of hearing what I was hearing in my head and then getting that on tape. It feels good. I have doubts about a lot of things, and I’m worried about people misinterpreting it—all of that stuff—but I am proud of this record.

VS: Speaking of “economical,” I was thinking while I was listening to the record—and after having recently read another essay you wrote for The Talkhouse about the potential of selling a letter Kurt Cobain wrote to you—about just how much I admire your transparency about the economics—the often dispiriting and difficult economics—of being a musician. It’s something I think you illustrate beautifully and really purposefully in When I Grow Up [Hatfield’s memoir] as well. I’ve always felt the pressure, as art-makers of any kind frequently do, to keep quiet about how much I’m being paid, if I’m even getting paid. There’s just a general sense, I think, of it being something immoderate to discuss. But you’re so up front with it, and I find it so refreshing, because it seems like now more than ever is the time for artists to talk about this kind of stuff openly and honestly.

JH: And our President hasn’t released his tax records!

I have this fantasy of writing a book that details, down to the last penny, the real expenses of this career—recording, going on tour, all of it. I think it would be really illuminating for a lot of people.

VS: I think that’d be fantastic, because it really isn’t something people talk about and it’s something we should be talking about. I also think a lot of people are under the impression that if someone’s on a stage, or if they consider a person to be famous, it must follow that that person is rich.

JH: Exactly! That gets my blood boiling. Whenever you see or hear musicians speaking out about their music being downloaded for free off of some illegitimate site, someone will always be there to say, “Well, they make all their money on the road anyway.” I would just like to show those people how much money I make on the road. I am not rich. Not everybody is bringing in Katy Perry money just because they, too, are on the road.

The other issue is that there are people who just don’t do well on the road. I, for example, tend to start to break down physically after a certain amount of time on the road. It’s not good for my health. I always lose a lot of weight. I get these epic sicknesses. I come home looking and feeling terrible. It’s less and less easy to do. And no one accounts for that, either; the financial toll and the physical toll.

VS: Right. At the same time, I feel very lucky that we, as creative people, do have outlets through which we might address the chaos we find ourselves in; the chaos that Pussycat is adumbrating and the cultural moment it’ll be entering when it’s released. Like, I don’t know what a dentist is doing with this maelstrom.

JH: I guess we are lucky. I don’t know if it’s doing any good, but there is something about sharing the alarm, sharing the concern. There’s a comfort in knowing that so many people share the concern. And that’s not nothing. And, you know, good things do happen once in a while, encouraging things, despite what’s going on overall.

VS: Right, and I think you just have to savor those smaller victories. They’re going to have to be what buoys us in—

JH: The wreckage. The wreckage! How are we going to get through it? Are we going to get through it? I think it’s going to make nihilists out of a lot of people.

VS: I don’t disagree with that. I also think nihilism has always gotten a bad rap…

JH: Me, too! I’ve always aspired to be one. These times are bringing me closer to that goal. It seems more pragmatic than anything else right now.

Juliana Hatfield Tour Dates

04/26/17 New York, NY at The Mercury Lounge

04/27/17 New York, NY at The Mercury Lounge

04/29/17 Lakewood, OH at Mahall’s

04/30/17 Columbus, OH at Ace of Cups

05/01/17 Chicago, IL at Lincoln Hall