Alan Hertz is one of the last disciples of jazz fusion – his drumming is similar to other great drum masters such as Billy Cobham and Tony Williams in that he plays with a complex and distinct style, erupting like a volcano when onstage. His style blurs across genres and rises above any supposed limitations of a single formula. As a member of jam supergroup Garaj Mahal, he helped to create a creative and enticing blend of funk and jazz, moreover the band’s improvisational talents rivaled that of other great fusion acts such as Mahavishnu Orchestra and Bitches Brew-era Miles Davis.

In more recent years, Alan Hertz’s output has slowed down, but he’s still collaborating with major session musicians in the studio and on the stage. I had a chance to speak with him recently and talk about his upcoming projects — here’s what he had to say.

When did you first start playing drums?

I started playing drums when I was two. My family was musical and there were all kinds of drums around, so as a toddler I would just go around banging on things. My pops got me a snare drum and cymbal for my second birthday. My dad was a singer/songwriter, he played country/oldies music.

Growing up, who were some of your major influences? Did you have any music teachers in your neighborhood or local community?

I always had a job – I always played with my dad growing up, so obviously my father. I would gig with him as a kid and he actually paid me for the gigs. When I made it into high school I got a job at the local music store in Sepastobol, CA called Zone Music. That’s where I met a guy named Tom Hayashi who got me into all the awesome drummers who had instructional tapes – guys like Dave Weckl, Terry Bozzio, Steve Gadd, Jack DeJohnette, Tony Williams. That guy Tom turned me onto jazz and that kind of alternative music. He also introduced me to Will Kennedy from the Yellowjackets when I was 15. Later on, I moved to LA at age 18 and Will became my teacher. I saved up some money and found a rehearsals space and we would practice there, he ended being my mentor for a good number of years.

Let’s talk a bit about your previous projects. You started out with Steve Kimock and Bobby Vega in the band KVHW. KVHW was a short lived project, but quickly became popular in the jam and college scene. How did that band originally come about?

I had been living in Los Angeles and hadn’t been making a living. I had to move back home into my parents’ house and ended up working at Zone Music again. So, Bobby Vega saw me at Zone Music and he hits me up and we started playing with Ray White. Ray also knew Steve Kimock and Steve and Bobby Vega were friends with Jerry Garcia – Garcia was a big fan of their playing, especially Steve. So, we started a band and climbed up the ranks quick because we knew Jerry Garcia plus Bobby had done session work for people like Etta James and Sly Stone. We got popular there for a second and then some political things happened and the band kinda dismantled, but who knows there still may be a reunion gig, we’re all still alive (laughs).

After KVHW disbanded, you joined Garaj Mahal, another supergroup jam band. I was first exposed to your drum virtuoso skills via Garaj. You guys had nine amazing releases on Harmonized Records and then went on hiatus. What happened with that band? How did everything start?

My friend was a big entertainment lawyer/manager and he worked with an amazing guitar player out of Chicago who had played with Sting and Joe Zawinul Syndicate – it was Fareed Haque. He suggested that I jam with Fareed and possibly do a project, I knew who Fareed was, said yeah and reached out to the bassist Kai Eckhardt. At first, we had a different keyboard player, but Eric Levy came into the picture later because he was Fareed Haque’s music student. But when Eric joined that was a match made in heaven. We decided to make the investment and bought the white van to travel the States in. I remember we were in Colorado and were like let’s stop renting vans and buy a van; it went from there.

But in terms of why I eventually left Garaj Mahal, I was getting some international gigs with Scott Henderson. I was enjoying traveling and having fun on those gigs, but at that same time Garaj Mahal needed to tour and had lined up gigs so they could keep working and make money. Sean Rickman filled in on drums and became a member after that.

You did mix and engineering work on all Garaj Mahal releases, as well. When did you first start doing audio engineering?

I’ve always been intrigued with audio engineering. I kind of use that as a stepping stone to hone my overall musical craft. I’ve engineered a lot of records…just this month I’ve done four or five records. Either tracking the album, playing on it or both — I recently did Scott Henderson’s new album. I played on Michael Landau’s album from 2018 and we may work on another one in the future.

You lived in in the Bay Area for a long time and recently moved to Los Angeles. How is the Bay Area different from SoCal?

There’s a difference between Bay Area and L.A in that there are more bands and group-oriented projects in Bay; Los Angeles is more for session musicians. There are so many musicians in LA who are on the level, you can throw a rock and hit ten really great drummers from your front door. It’s a sessions musician’s town.

Do you feel it’s easier to promote things at a grassroots level in NorCal as opposed to Los Angeles?

I think now with social media, with GoPros and everything streaming, location doesn’t matter as much. You just have to be relentless and really good. There are so many people promoting themselves online. I don’t want to come across snide and call people mediocre, but there is a lot of mediocrity out there. But it’s harder to hold down someone who is truly talented and empowered – you can live in a small town and make an amazing video that goes viral and reaches people in Los Angeles or New York.

Get your product right and make it on a truly amazing level first before promoting anything.

-Alan Hertz

You recently did some engineer work on the band Styx’s latest album. What’s your connection to that band?

My friend Will Evankovich produced the album and I had already worked with Tommy Shaw on the album The Great Divide — that was a great bluegrass album and featured Allison Krauss and Dwight Yoakam on a few tracks. We recorded that record in Nashville and did it ’70s style on 2-inch tape with a multi-track analog tape recorder. So, they liked how that turned out and my friend Will called and invited me to do the Styx record.

What kind of drum kit are you using these days?

I am a vintage instrument and recording gear fan. I have old sixties Grestch and Ludwig drums, sixties Fibes acrylic drums. I have a black sixties Fibes drum kit like Billy Cobham’s, but his is clear. Basically, I have multiple vintage Gretsch and Ludwig kits that I love. I love all the cymbals too, no bias there.

What about recording gear?

I like the same old stuff everybody likes…Neumann mikes, Neve microphone preamps, the Urei 1176 compressor, multitrack analog tape machines.

Let’s talking a bit about working as a professional within the music business. When you first became a working musician, did you have a mentor that taught you about the busines?

I would say my dad – my dad was paying me to play music in his band so I figured out an early age, wow you can get paid to do this. So that was cool…Bobby Vega was a mentor too. Vega because he’s an incredibly honest person and isn’t afraid to talk about money and music. I think being open and transparent about it is the best way to be. A lot of people will tip toe around the money issue – in the past I’ve been taken advantage of through vaguely worded record contracts — like in certain groups I was in, we basically signed away all our digital streaming royalties because we didn’t know the language.

Do you have any advice for young musicians looking to get started in the music business?

I don’t know if I can give advice or be part of that. Like Timothy Leary, I turned on, tuned in and dropped out. Friends who know me and my work will want to recruit me for their music projects. So, I guess I’d say to a young person is get known through word of mouth. I get work and pay my bills through word of mouth. Get out there and watch your favorite musicians in person and learn from them. Also, know when you’re truly ready to try and influence people. Don’t be mediocre just because you see someone else doing it and making quick money being mediocre; don’t replicate that – if you’re trying to get lucky that’s not very good odds.

Any last words about your projects or other advice?

In the sixties, there were roughly 3.3. billion, now there’s 7.5 billion; our population has more than doubled. Population is growing and doesn’t seem to be stopping. So, this also means your chances of notmaking it have also doubled. If you’re doing music for the right reasons and love to play, you’ll get it. But if you’re doing it for money, you’re setting yourself up for a letdown. If you can do it because you want to keep getting better and better, go for it, don’t get discouraged. The love for music is the main part of it. I still play every day and feel better about my day after playing.

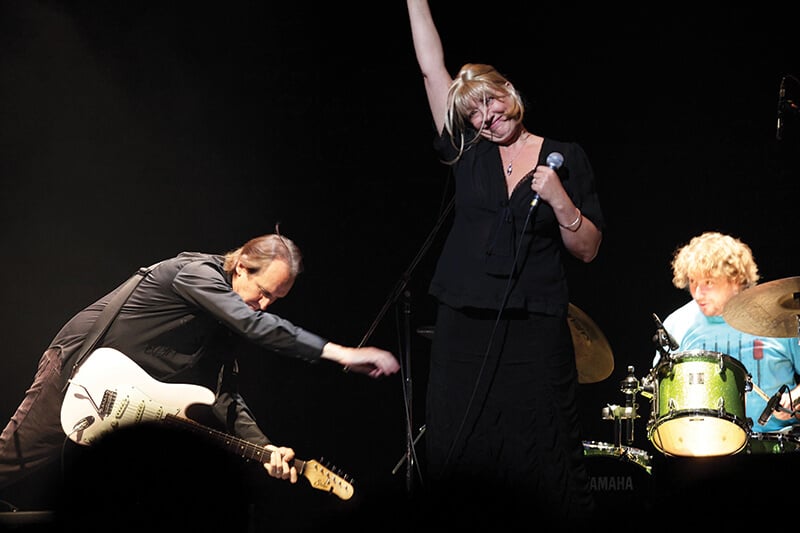

**photos courtesy of the artist