“Suddenly I was face to face with quite the dilemma: Hire a world-class producer with my own cash or suck it up and record the album on my own.”

I’ve been recording my own demos for years now, slowly amassing an unnecessary amount of gear with little intention of anyone ever hearing what I create. Insecurity and laziness have held me back for a long time, with only a couple of recordings ever leaking out into the world. Ironically though, those few home recordings have actually been my most commercially successful, but having made my last record with Greg Wells and Eric Valentine, and the one before that with Tony Berg and Blake Mills, the bar of my recording career is so high that I couldn’t accept that my next album would be produced by…me.

Let me take you back to Christmas 2017: I was on the phone with my manager being told I had just been dropped by Warner Bros Records, weeks before I was due to start my fourth studio album with the one and only Butch Walker. There went the recording budget, and my chance to make one of the coolest records of my career…

Suddenly I was face to face with quite the dilemma: Hire a world-class producer with my own cash—knowing full well I had more chance of winning an Oscar for Best Actor than making that money back, especially in 2019’s musical climate—or suck it up and record the album on my own. I sat there spinning in the chair of my home studio in Los Angeles, surrounded by thousands and thousands of dollars’ worth of analog outboard gear, microphones and guitars— the majority of which was paid for with Warner Bros. advance money, gracias!—, and decided that if I had all this gear already, I should probably just grow a pair and get to work.

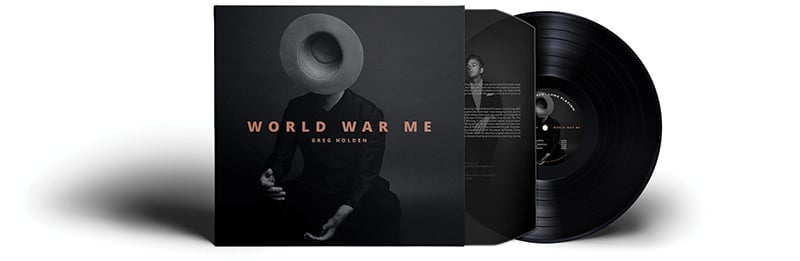

And so began an epic Hollywood-esque journey of self-doubt, self-loathing and crippling insecurity, slowly evolving into occasional eruptions of confidence, growth and eventually, pride. Somehow I’d eluded the guards, crossed the raging river, scaled the highest mountain, slew the dragon and rescued the princess from her tower. A year later, she was feeding me grapes and my fourth studio album World War Me, was on its way to my buddy Cian Riordan’s place to be mixed.

I started writing and demoing the album long before I knew what it looked like or who I was going to record it with. So, by the time I’d decided to do it myself, a lot of the foundational elements were already there, including all of the songs. Guitar parts, vocals, backing vocals, piano parts, most of that was already recorded as I usually try to track my demos as best I can out of fear of the dreaded “demoitis.”

All I really needed to do was work on the arrangements, re-record some of the vocals and acoustic guitars—since demoing the tracks I’d made considerable upgrades to API 500 Series Neve 1073’s microphone pre-amps and Royer R-121 Ribbon Mics—and then hire great musicians to fill in the gaps and find the overall vibe of the record. Roger Manning Jr (Beck, Jellyfish) really helped discover said vibe with his keyboard wizardry and mystical sounds. I love to program drums myself, as it really helps me build a song if I can hear a good drum track. I tend to get intensely detailed, too—secretly I wish I was a drummer— adding ghost notes, velocity irregularities, and even sometimes occasional mistakes to make them sound more realistic.

I separate each individual drum, add a little distortion to the snare and high hats, some tape delay to the cymbals to make them sound less weak, and then send everything through an API 2500 stereo compressor with a little decapitator on there to give the drum track some balls. Any professional is probably reading this and laughing at my conviction that I know what I’m doing, but for me, if it sounds good in my ears, I’ve succeeded in my mission. That is until I compare it to something else and spiral into insecurity…

I had every intention of replacing all the programmed drums for this record, but in the end, only replaced a few. I had my buddies Mark Stepro and Frederik Bokkenheuser record real drums on “Nothing Changes,” “On The Run” (produced by Butch Walker) and “Something Beautiful.” These were recorded at Boulevard Recording in Hollywood, CA (engineered by Clay Blair) and Ruby Red Studios in Santa Monica, CA (engineered by Todd Stopera). Some songs needed real drums, some didn’t and I already loved the way they sounded. I tried not to be too precious about “real” drums on this record for a change. It was a good test in comfort zone management.

I recorded the majority of the vocals using my Pearlman TM-47, which is my go-to vocal mic and the best replica of a U-47 I’ve ever heard. I have quite a boomy voice when I’m singing the lower notes, and this mic works really well for that. I used my Shure SM7b (the best mic in the world if you ask me) for a couple of the more vocally aggressive tracks because it just sounded better to me.

All the vocals went through either the Neve 1073 or my UA LA610 Mk II, and then through my UA1176 compressor because nothing beats an 1176. I ran the bass straight in through the Neve 1073 (no amp) and switched out the 1176 for my Retro Doublewide because I just thought it sounded cooler—no skillful intentions there. I tracked the acoustic guitars with one R-121 close up on the neck, and my TM-47 about a foot away through the Neve 1073s.

Everything was tracked using my wireless keyboard and a stool on the opposite side of my studio, wrapped in diffusers and gobos. No engineer, just me and a lot of yelling. The process of recording this record myself was incredibly challenging based on my level of experience in making full-length albums (approximately no experience), but it was equally rewarding. At first, I really struggled with getting the right sounds in my small home studio. I’ve had it professionally fitted with sound absorbing gobos and diffusers, but I live really close to a freeway, and so the more I gained up my microphones for the soft vocals and more intricate piano and guitar parts, the more noise I’d hear—all the padding in the world isn’t going to stop that.

Stack those tracks over and over and you’ve got yourself your very own orchestra of Los Angeles traffic and meowing cats, that sound like they’ve been crushed through a flanger pedal. So, balancing that microphone gain level, especially with compression, was difficult, but not impossible. EQ helped, and I used the Waves NS1 plug-in a lot, which acts as a very easy-to-use gate. In the end, though, I came out of this process with more knowledge of EQ, mixing, microphone placement, my room’s limitations, and most importantly, my own limitations.

The real challenge was to know when to ask for help—which is a running theme in my life. No matter how many world-class musicians I’m friends with, I kept trying to play all the instruments myself. No matter how many world-class mixing engineers I’m friends with, I figured I could just mix it myself—how hard could it be? Then, when it sounded like I’d set all my gear on fire and recorded the whole thing on my iPhone, I plummeted into the depths of hell, only to be rescued by my friends. Having someone else mix the record was vital to this whole process, and having incredible musicians on it like Roger Manning Jr, Mark Stepro, Whynot Jansveld—Whynot also mastered the album—and Frederik Bokkenheuser really brought it up to the standard I have grown accustomed to. I’m super fortunate and grateful for those guys.

On to album #5…

Follow on Twitter @gregholden