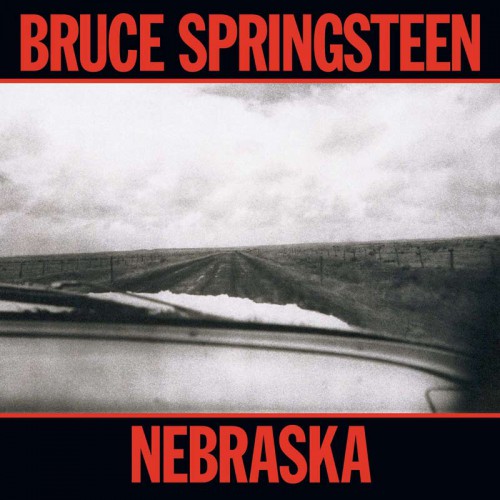

Independents Day: Bruce Springteen’s Nebraska Opens Up A World Of Home Recording

In January of 1982, Bruce Springsteen recorded a group of fifteen demos in the bedroom of his house in Colts Neck, New Jersey. The last three albums he had recorded with the E Street Band had each taken an extraordinary amount of time to reach completion. Frustrated, Springsteen decided to come up with a new strategy for the recording process. Instead of recording demos straight onto a boombox, now the songs he was recording would be high quality, professional grade demos with overdubs and effects, maybe a little percussion added to show the band just what he wanted.

A month earlier he had sent his guitar tech Mike Batlan to buy an easy-to-use cassette recorder that he could record overdubs on. Batlan came back with a Teac/Tascam Portastudio 144 4-track and two Shure SM57 microphones. After doing some additional acoustics work on the bedroom, The Boss got started.

Towards the end of the River tour, after the election of Ronald Reagan, Springsteen began talking about Woody Guthrie and what he stood for. He talked about reading Joe Klien’s biography Woody Guthrie: A Life and what it taught him about his country. He said his next song wasn’t a song for schoolchildren to sing. “This song is a fight song,” he said. Then he proceeded to go into “This Land Is Your Land.” At home after the tour, he watched Terrence Malik’s movie Badlands, about Charlie Starkweather, who had gone on a two-month long killing spree through Nebraska and Wyoming, killing eleven people and two dogs. Guthrie and Starkweather were two men who had done a lot of thinking about what America actually was and what it meant. The two men would have a profound effect on the songs Springsteen was writing. These songs had the dark insides of Guthrie’s most harrowing material, like “1913 Massacre” and “Pastures of Plenty,” songs about children killed by union-busters and hunger and desperation. Like Guthrie, Springsteen wrote an outlaw ballad. He called his “Starkweather.” It took images directly from Badlands. He later changed the name to Nebraska.

In 2015, as nineties revivalism is coming around, it’s hard to appreciate how dark the 1980s were in America. But it’s when everyone realized cocaine was addictive. Home recording hadn’t progressed much beyond recording one performance at a time. Alan Lomax thought modern home recording equipment was primitive (unsubstantiated). Jack White thought it was perfect (possibly). There were various ways to record yourself, but everything had to happen at one time in one take. Musicians recording demos at home was not standard practice. They went into the studio and showed everyone else how the song went.

In 1979, TASCAM came out with the Portastudio 144. It was affordable and you could multi-track. And you had four tracks, just like the Beatles had for Sgt. Pepper! Processes like mixing had been simplified. The damn thing was easy and almost foolproof. It was perfect for Springsteen and Batlan.

the same 4-track model that The Boss recorded Nebraska on in 1982

So, Springsteen and Batlan set up the new, cutting edge, thoroughly modern home studio to record demos for what would be Springsteen’s oldest sounding songs yet (ever). These demos, of course, became the album Nebraska. Most of the songs on the album were recorded on January 3, 1982. The demos were mixed through a Gibson Echoplex onto the aforementioned boombox, only now it had fallen into a river, died and came back to life after getting hosed off. That cassette is what Springsteen played for his manager and the E Street Band.

All hands gathered at the Power Station recording studio in New York City to record the songs Springsteen brought in. As he later said, the more he tried to add to them, the more he made them worse. According to Springsteen’s long-time engineer Toby Scott, Springsteen would pull the cassette out of his coat pocket and say, “I want it to sound more like this.” Eventually, he asked Scott if they could get a master off of the cassette. And eventually, three mastering studios would be listed in Nebraska’s credits.

Nebraska was promoted as “Basic. Brilliant. Solo Springsteen.” The album’s liner notes notify the world at large that this Bruce Springsteen album was “(r)ecorded in New Jersey by Mike Batlan on a Teac Tascam Series 144 4-track cassette recorder.” Cleary, the story being sold was that Springsteen recorded the album all by himself at home, like Paul McCartney had with McCartney (McCartney, however, was using very different and much more sophisticated equipment). Imagine being one of those musicians starting out in the early 1980s and you’ve just spent a small fortune on recording equipment. You and your buddies have been playing around with this Portastudio, recording some stuff to try to hustle gigs or impress the guy/girl/guygirl you’ve been trying to talk to for weeks. And then the biggest fucking rock star on Earth releases an album that was made on the same beginner-level contraption with the red, white and green knobs you’ve got in your bedroom. You’d look at it a little differently, right?

The success of Nebraska strictly as a recording project was the “emperor has no clothes” moment. You could make a record at home, a real one that, and if done right could be good enough to be released on Colombia Records. Marginalized musicians went from metaphorical finger paint (boombox) to brushes, canvas and a pallet. The freaks had the keys! Underground music exploded; from Daniel Johnson to Ween to Neutral Milk Hotel to Iron & Wine to Bon Ivor and on and on. It became the de facto home studio device in early hip-hop circles.

Vermont guitarist and proud independent musician Scott Tournet is an artist who recorded several great and criminally underappreciated albums of material on Portastudios, parallel to his career with Hollywood Records recording artists Grace Potter and the Nocturnals, who did not record on Portastudios. “Using the Portastudio was great for me because it gave me as much time as I wanted for experimenting. Experimenting on my own, free time and not on studio time. It also helped me spend necessary time working on my vocals. It’s really helpful if you’re shy about singing or playing in front of other people.”

In hindsight, it seems fitting that it was Bruce Springsteen who expanded the possibilities and reach of the Portastudio. Think of your image of Springsteen and what he stands for. Shouldn’t that be the guy to popularize a device that took the need for expensive studios away? He opened up the Myers Park Country Club for everybody.

Including me. Like many musicians who had been frustrated by an inchoate creative vision, when you read “Neil Young records everything at once and he never edits. Genius!” or ‘Bruce Springsteen wrote some songs and recorded them in one night on the beginner recording deck. People love it!” I turned my ear to the siren’s calls of Neil Young and David Briggs and Bruce Springsteen. I tried many times to get one Nebraska quality song. That didn’t end well. There were no survivors. My point is that the Portastudio is the tool, not the talent. Even Neil Young (now more than ever) needs an editor. Find the way that works best for you. Let that become the new story.

Author’s post-script: Seriously, check out Scott Tournet’s Everyone You Meet is Fighting a Hard Battle. Then buy it. I’ll autograph it.