Envelope Generators, or EGs, create a control signal that rises and falls over time when a note is triggered. In a synthesizer, that signal can control an amplifier to shape loudness changes over time. It’s also common to raise and lower a filter’s cutoff frequency, so brightness changes over time. Pitch envelopes are great for creating realistic drums and interesting synth patches. But there are dozens of other things we can control with EGs and having multiple envelope generators allows control of multiple parameters in different ways.

Three common kinds of Envelope Generators are ADSR, A-Gate-R, and Decay.

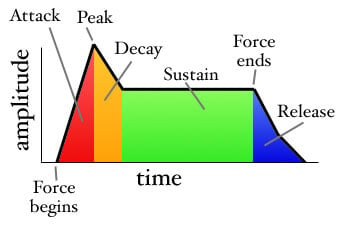

An ADSR EG gives you full control over attack time, decay time, sustain level, and release time. Attack controls the time it takes to go from 0 to 100% level. Decay controls the time it takes to go from 100% level to the sustain level. Sustain controls the level where the note settles; set it low for more punch, or higher for a more compressed sound. Release controls the time it takes to go from the sustain level back to minimum after the note is over.

An A-Gate-R EG allows control of attack and release times and assumes sustain level at maximum. Some EGs of this type allow you to switch from gate to trigger mode and will begin to release as soon as the attack is over.

A Decay EG assumes an instant attack time and no sustain; you only control decay time. For 90% of percussion sounds and plucked stringed instruments, that’s really all you need. The classic Acid House bass machine, the Roland TB-303, had a simple Decay EG. Decay EGs are also great for filters.

Let’s think for a moment about the physics of how acoustic instruments produce sound. You can divide them into two camps: instruments that allow players to keep feeding energy into them so they can sustain, and those that only allow energy at the beginning of the note. Wind instruments, such as woodwinds, brass, pipe organs, and the human voice, can all sustain as long as the wind keeps coming. Similarly, bowed stringed instruments, can sustain as long as the bow keeps moving. Electronic instruments keep sustaining as long as you pay the electricity bill!

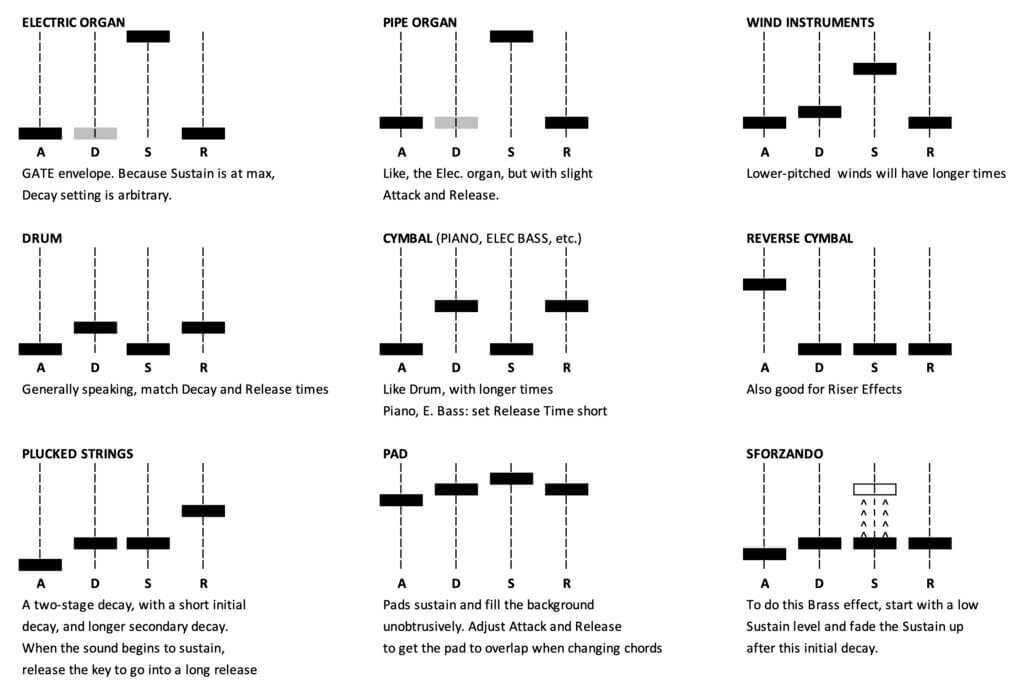

Electric organs use a gate-type envelope, with minimum attack and release times, and maximum sustain level. If you are using an ADSR envelope, the decay setting is arbitrary, because sustain is at maximum. Pipe organs are similar, but because the air in the pipe has inertia, it takes a few milliseconds to get it to move and to stop moving. For this reason, use short attack and release times—and a ton of reverberation. Since the lower-pitched pipes are longer, they have longer attack times than higher pitches.

Wind instruments also have a column of air to move—a trumpet uses about five feet of tubing, for example. Once the air gets going, it doesn’t take as much force to keep it sustaining, so there tends to be a slight drop in level during the note’s sustain as compared to its attack. Start with medium-short attack and release times, set the sustain level relatively high, say 70–85 percent, and match the decay to the release time. Again, lower instruments have longer air columns, so lengthen the attack, decay, and release times. Tuba is two octaves below the trumpet, so the air column is four times longer and times should increase proportionally.

For plucked, hammered, or strummed strings, mallet instruments, and most percussion sounds, all the energy is put in at the start of the note and loudness necessarily decreases over time. There is an instant attack time, and no sustain level. Because decay time is the only thing you need to adjust, you can use a Decay EG, or if using an ADSR EG, set attack and sustain to minimum, and match the release time to the decay time. That way, it won’t matter whether you hold the note, or let it go early. For Bass, Guitar, and Piano sounds, you probably want long decay and relatively short release times. This simulates damping by the player at the end of the note.

These are just some examples of how to manipulate your synth’s envelope generators to approximate sounds of instruments you know and love – but of course half the fun of playing synthesizers is to experiment and come up with brand-new sounds.