In an era where creative or commercial success is possible without the need for physical hardware beyond a computer running the right application, one could be forgiven for believing there is no longer a need for seemingly antiquated analog technology in music production. However, increasing numbers of musicians are enjoying the unique experience of exploring the distinctive properties and authenticity analog synthesizers have to offer.

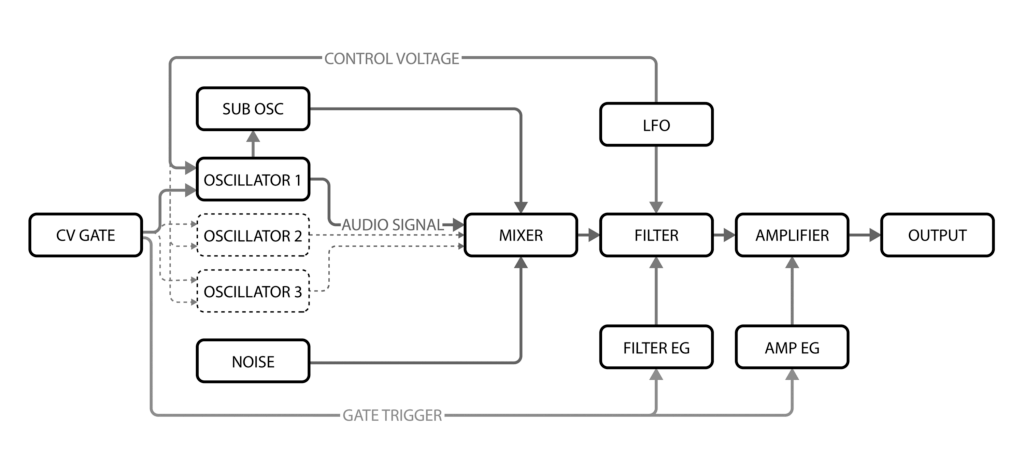

While aimlessly tweaking knobs, sliders and switches can unquestionably be fun, it is of course massively advantageous to understand both the core principles at work, and what tools are on offer to assist in crafting any specific tone that might be envisioned. To fully grasp the intricate workings of the analog synthesizer it helps to comprehend and visualize the signal path on its journey from input to output, and how this flow utilizes various elements of the circuitry which generate and shape sound waves.

Oscillators: Where It All Begins

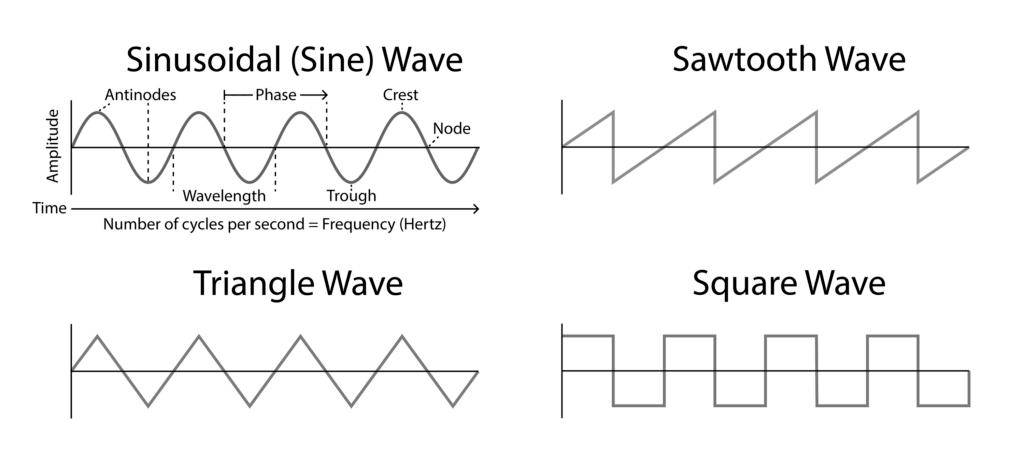

Analog synthesis begins with at least one Oscillator to produce a repeating waveform, the frequency of which is determined by voltage. The most fundamental waveform any Oscillator generates is the most uniform wave possible. Made up of a single element, Sine Waves are smooth and clean, creating whistling tones.

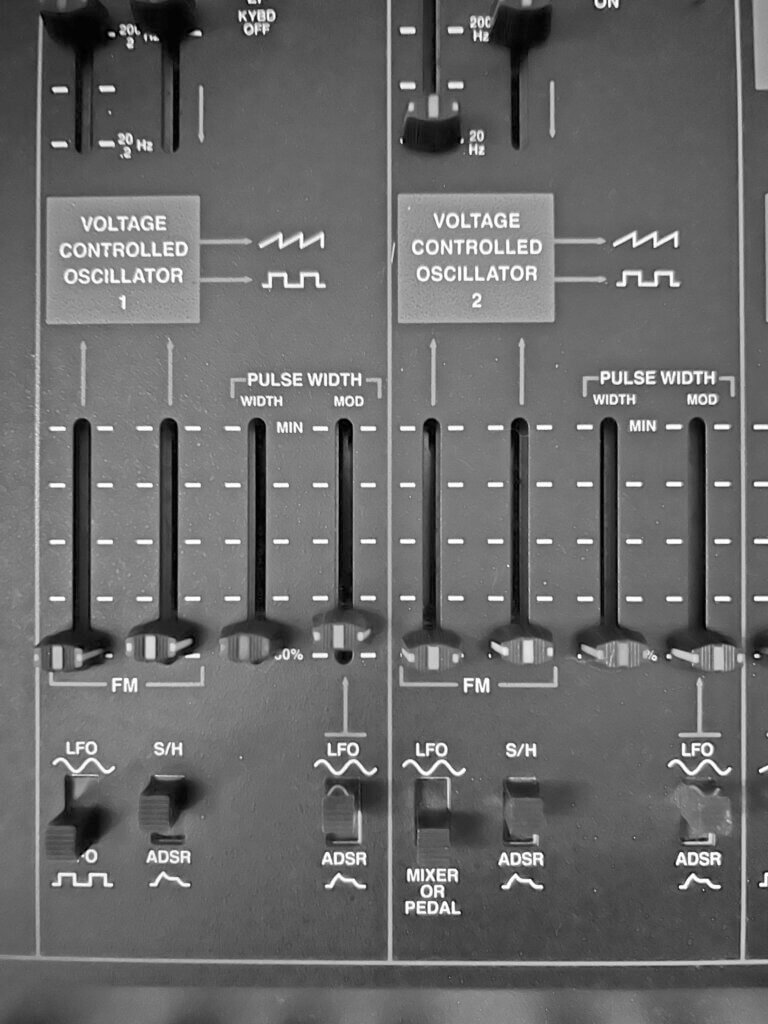

A Voltage-Controlled Oscillator (VCO) can also introduce harmonics or other elements to offer alternative waveform shapes, each augmenting the underlying sound. Square waves generate a harsh tone heard in things like smoke alarms, Triangle waves deliver bright yet hollow timbres, and Sawtooth waves produce an unmistakable buzzing sound.

Especially useful in machines with only one Oscillator, a Sub-Oscillator duplicates and halves the frequency of its parent Oscillator and is responsible for much of the warmth found in the bottom end of analog synths. A random waveform with equal energy across all frequencies can also be generated resulting in a hissing or static sound known simply as Noise.

By varying the Control Voltage (CV) to the VCO, the frequency of the waveform alters the pitch of the tone. CV can be provided from an external source, but the standard for most modern synths was set in 1970 with the release of the Minimoog, the first commercially available synthesizer to provide proportional voltage to VCOs via a built-in piano-style keyboard.

An alternative to VCOs, DCOs (Digitally-Controlled Oscillators) set frequencies by dividing down a digital timing signal usually generated by a microprocessor. Despite being digital in nature, it is not uncommon to find DCOs in analog synthesizers. VCOs produce subtle variations in frequency and waveform due to factors such as temperature, aging of components, and power supply fluctuations. This results in a slightly more organic, dynamic tone. It’s not uncommon for VCOs to have to warm up, and periodically drift out of tune. VCOs are often preferred by musicians who value more character in the sounds they produce, whereas the consistent nature of DCOs are commonly preferred by those who strive for a more precise and stable sound.

Filter Those Frequencies

Once the initial waveform is selected it is common to shape it further, usually by means of a filter. These allow certain frequencies to pass through unaltered while attenuating or cutting others completely, hence the term Subtractive Synthesis. By manipulating the frequency response of a waveform, musicians can shape the embryonic sound in unique and creative ways.

The most common type of filter found in analog synthesizers is the VCF or Voltage-Controlled Filter. A VCF shapes the waveform by altering the amplitude of different frequency components within the signal. There are several types of VCFs, each with unique characteristics. Of these the most common is unquestionably the Low-Pass Filter (LPF) which permits lower frequencies to pass through while cutting higher ones, helping to create a warmer, more mellow sound.

ARP Odyssey oscillators section

Predictably, a High-Pass Filter (HPF) allows higher frequencies to pass through and reduces lower frequencies. HPFs help sculpt brighter, more attention-grabbing sounds that can more easily cut through a mix, such as those used for riffs in electronic dance and pop music. Band-Pass Filters (BPF) preserve a range of frequencies known as the passband and reduce those. The opposite of a BPF would be a Band-Stop Filter. Notch Filters (NF) reduce a precise frequency range, the control of which is dictated by a controllable algorithm called the Quality Factor (Q Factor).

Amplifiers allow for a more dynamic performance by providing control over the volume and sustain of the now filtered signal and are the final building block in any analog synthesizer. The most common amplifier found in analog instruments is the Voltage-Controlled Amplifier (VCA) which responds to a control voltage to adjust the overall amplitude of a sound.

Modulation Magic

In addition to VCAs, many analog synthesizers also include Envelope Generators (EG) to supply a Control Voltage that changes over time. Not always limited to amplitude, this CV can be used to influence the frequency or other parameters of a sound. Envelope generators typically have four stages: Attack, Decay, Sustain, and Release (sometimes simply labeled ADSR). During the Attack stage, the voltage rises from zero to its maximum level. A fast or short attack time produces a more percussive start to a sound, where a longer attack generates a swelling sound that gets progressively louder. At the decay stage, the CV falls from its maximum level to that set by the upcoming Sustain stage, which holds the Control Voltage at a constant level until a Gate signal is received by a sequencer, arpeggiator or by the release of a key. It is at this point the Release stage begins, and the Control Voltage falls back to zero at the chosen rate.

EGs can also be used to modulate the frequency or filter cutoff of a sound, often employing a Low Frequency Oscillator (LFO) to add fluctuations in pitch (vibrato), amplitude (tremolo) and/or for more dramatic filter sweeps. Their flexibility and versatility make them extremely valuable when it comes to modulation, allowing for the creation of complex, evolving and expressive sounds.

Have Fun

The sonic exploration and performance possibilities of analog synthesizers are practically endless. It is hoped that the above provides a foundation in understanding, and in doing so may help to demystify this truly powerful and compelling area of sound design.