New laws are forcing many guitar manufacturers to rethink how they source high-end tonewoods, including Indian Rosewood, from around the world

Guitar makers and distributors are scrambling to comply with new international trade restrictions on rosewood that went into effect in January of this year. The new regulations cover all 300 species of the exotic lumber including Indian rosewood, one of the most popular tonewoods for high-end acoustic guitars, coveted by musicians for its defined low-end bass tones and deep red grain finish.

At a summit in September, 181 countries participating in the Convention on Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) agreed upon the regulations in response to a spike in illegal rosewood trafficking over the past few years. This increase is due to a booming demand for luxury furniture in China, which imported $2.6 billion dollars of rosewood in 2014, a 70 percent increase over the previous year, according to a report by conservation and research group Forest Trends.

CITES upgraded rosewood to its second most restrictive classification, identifying it as a species that is in severe danger of becoming extinct without strict trade oversight. American guitar makers have become attuned to CITES’s decisions in recent years, after an amendment to the Lacey Act passed in 2008 made all restrictions on plant life under the CITES treaty legally binding in the United States.

Individual guitarists traveling with rosewood instruments are exempt from the regulations, but manufacturers and distributors must now provide additional administrative paperwork and buy new permits to ship rosewood across most international borders—while also confronting the feasibility of importing exotic tonewoods in the future.

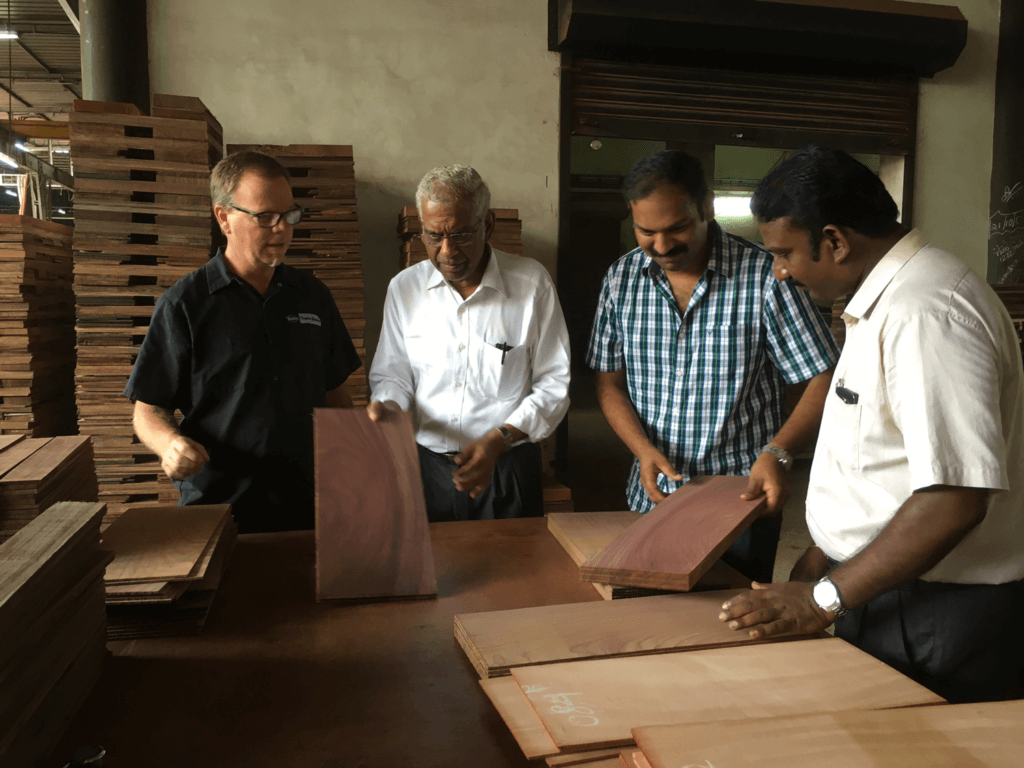

“With the new law, buying and selling rosewood is going to become much more difficult,” says Charlie Redden, the director of supply chain at Taylor Guitars.

Redden says Taylor is rethinking whether to use rosewood in certain upcoming models, but expects the company to be able to absorb any additional costs without passing them on to consumers. He does, however, anticipate tonewoods from forests in Africa, Southeast Asia and Central and South America to become increasingly difficult to source because of further restrictions.

“At the [CITES] convention some of the NGO’s who organized this listing told us they’re working on ebony being the next one they list,” says Redden.

Chris Herrod, sales manager at tonewood distributor Luthiers Mercantile International, Inc., which supplies both large manufacturers like Martin and Taylor as well custom builders, says the new restrictions may already force the company to cease shipping Indian rosewood internationally.

“For small orders, which are the bulk of our business, it’s not really feasible right now,” says Herrod. “We’re looking at alternatives but that is sort of a work in progress.”

Herrod is frustrated that Indian rosewood is listed in the new CITES classification because he says Indian rosewood is not an at-risk species and many of India’s forests are certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC).

photo courtesy of Taylor Guitars

The FSC is an independent organization that aims to ensure forests are responsibly managed by sending auditors to inspect logging sites. But even if a forest is FSC certified, Herrod admits there are still steps along the supply chain where things can go wrong if distributors aren’t diligent. Once trees are logged, for example, sellers often mislabel one restricted or banned species as a less regulated wood with similar characteristics. Customs agents often can’t tell the difference, which is likely why CITES decided to list all rosewood species without exemption.

In addition to jeopardizing the rosewood population, this illicit trade has had devastating effects on forests and the people who live in them. In Thailand, National Geographic reported that the rampant poaching in one of the country’s national parks has led to violent clashes between government rangers and poachers. Cambodia, Madagascar and Honduras have also been afflicted by illegal logging in recent years, which damages local ecosystems and “robs communities of resources they depend on for subsistence purposes,” says Forest Trends researcher Naomi Basik Treanor, who studies the effects of deforestation and the illicit timber trade around the world.

As a result, environmentalists have been pushing governments even harder to protect and preserve these forests.

“If these [rosewood] species are important to the sound of the guitar and the tonewoods are irreplaceable, [guitar manufacturers] are going to have to find a way to cultivate them somewhere else and make a long-term investment,” says Treanor. “Or they’re going to have to switch to species that are more sustainable.”

In the same way guitar makers turned to Indian rosewood after Brazil banned the export of its own coveted rosewood in the late 1960s, Redden at Taylor says it’s possible that domestic species could one day replace exotic tonewoods as the industry standard.

“If the trends continue with rosewood and mahogany, then manufacturers like us are going to start using woods like walnut and maple,” says Redden.

Taylor already has a wide catalogue of models made from these woods. One of the manufacturer’s main domestic suppliers is Pacific Rim Tonewoods, a specialty mill that cuts spruce, maple and walnut in the Pacific Northwest as well as koa in the forests of Hawaii. The company is committed to responsible sourcing and handpicks each individual log it sends to be cut.

“Because we’re a mill, we do best business-wise when we buy the right logs and follow them through every step of the manufacturing process until we ship them to the guitar makers,” says Steve McMinn, the company’s founder.

Still, domestic timber is not without its own complications. Systematic clearcutting and logging on Native American lands have long been problems for the lumber industry in the Northwest. To ensure its commitment to environmental stewardship, McMinn says the company has plans to work with private and public landowners to plant, grow and manage domestic species as well as mahogany and ebony on the Hawaiian Islands.

“We will be deeply involved with forestry within the next couple of years,” says McMinn. Adding that, “We’re trying to develop strains that are better for instruments and figure out how to get those grown.”

While some guitarists may scoff at the idea that walnut or maple could ever be an acceptable replacement for rosewood, Redden thinks they can be convinced.

“We’re going to try to change the whole perception of this wood. It’s still beautiful sounding and it’s still beautiful aesthetically,” says Redden. “And for the first time ever we can also talk about it being sustainably harvested and responsible.”