A Trillion Data Points: The Growth Of Music Analytics

And Why Knowing Your Band’s Data is Crucial

Everyone knows that music has made the leap onto the Internet. But perhaps no one better understands how drastic this leap has been, or what its implications are, than Alex White, co-founder and head of music analytics company Next Big Sound.

“I think the top-line number of over a trillion plays in the first half of [2015] alone is a really significant milestone for the industry,” he comments.

That’s a trillion plays online in six months – a trillion data points to be measured and interpreted by everyone from fledgling artists seeing where they’re popular to major labels looking to sign the hottest new talent. Let’s take a look at how we got here and where music analytics stands now.

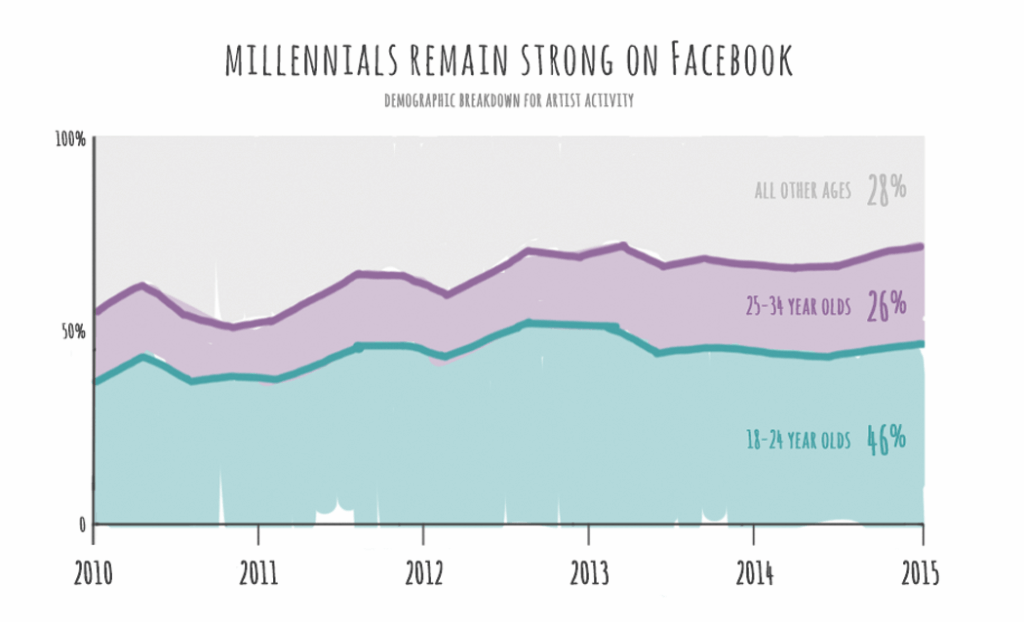

chart originally published at https://www.nextbigsound.com/industryreport/2015summer

The Properties of Songs

Though music analytics today focuses on artists’ performance in the market, the field has its roots in data scientists trying to categorize songs based on their acoustic properties. Two early pioneers were the Music Genome Project and Hit Song Science. The former, which used an algorithm of sonic traits called “genes” to determine similarities between songs, was the brainchild of Tim Westergren, who founded Savage Beast Technologies in 2000 to market the product as a music recommendation service at brick-and-mortar stores. When the company floundered in the mid-2000s, it changed its name to Pandora and applied the Music Genome Project to the creation of individualized digital radio channels.

Hit Song Science, a product of Barcelona-based Polyphonic HMI, sought to take its formula one step further than the Music Genome Project, attempting to predict songs’ success by comparing them to past hits. The software made some waves when it accurately predicted that Norah Jones’ 2002 debut album Come Away With Me would be a commercial smash, contrary to the expectations of many industry insiders. Like Savage Beast, though, Polyphonic struggled to find a market for its product, perhaps because of its artificial nature. According to a Harvard Business School case study on Polyphonic, “initial sales pitches had met with considerable resistance, and early news reports on Hit Song Science voiced some concerns,” many of which expressed skepticism over a machine’s ability to judge a song’s emotional impact.

“Both Savage Beast and Polyphonic HMI were a little too early to the music recommendation game and both companies were approaching bankruptcy,” said Polyphonic’s former CEO Mike McCready. “The music recommendation product just wasn’t catching on.” In an industry that has traditionally relied on “golden ears” and the subjective tastes of legendary A&R executives to make hits, it’s easy to see why the idea of reducing songs to mathematical properties was rejected. By directing the Music Genome Project towards the consumer, though, Pandora created a highly marketable music recommendation engine that laid the foundation for streaming services to take over the music industry. Apple Music and Spotify recommend music to users in a similar fashion, and Spotify in particular has embraced the analytical method, using algorithms to generate not just customized playlists but also, as of November, concert recommendations.

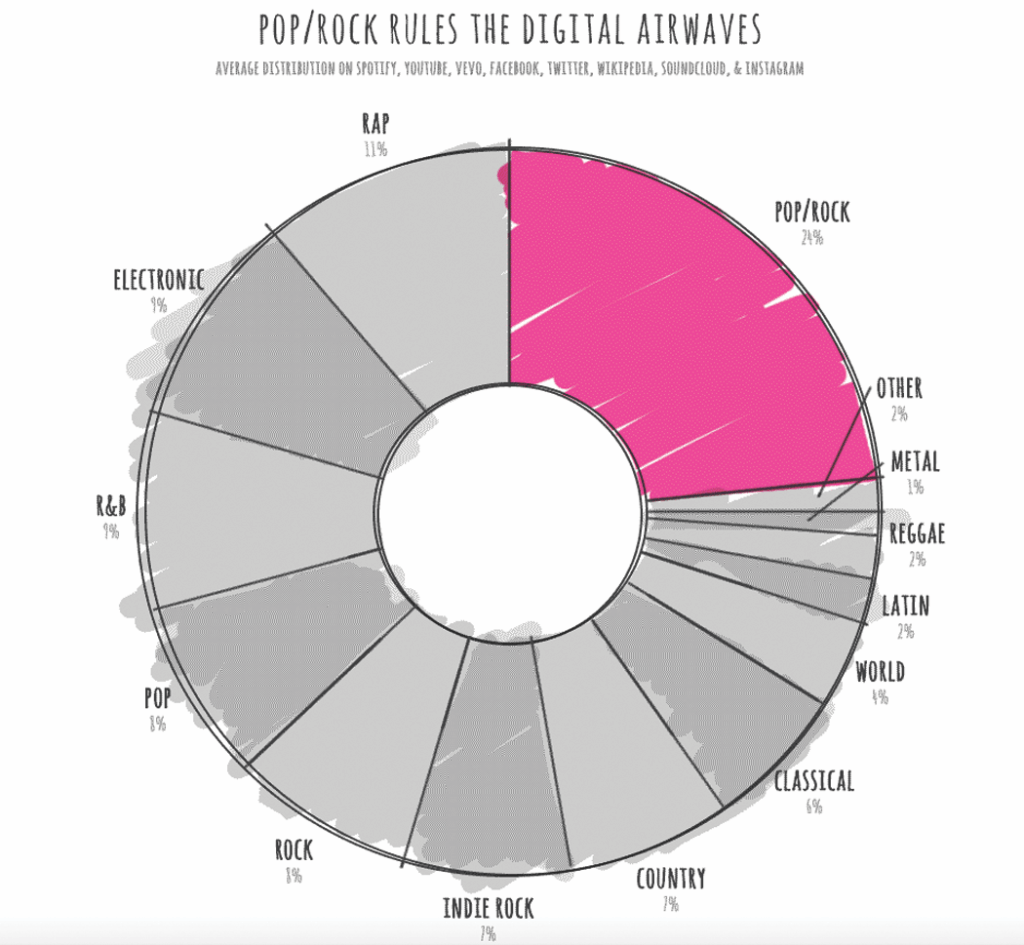

chart originally published at https://www.nextbigsound.com/industryreport/2015summer

Data Moves Towards The Market

With the wholesale movement of music to the Internet and the advent of social media has come a flood of listener data that wasn’t available when terrestrial radio and record stores ruled. The focus of music analytics has accordingly shifted toward making sense of this data, with an eye toward predicting artists’ future successes based on their current performance across as many platforms as possible. Such is the growth in this market-based music analysis that in the past two years, each of the industry’s leaders was acquired by a streaming service in a multimillion dollar deal: Spotify bought The Echo Nest, Apple Music bought Semetric (creator of Musicmetric), and Pandora bought Next Big Sound.

Alex White said that the acquisition was initially driven by his company’s attempts to access Pandora’s listenership data. “In October of 2014 they opened up their artist marketing platform, which was the first time they’d shared their data publicly, so that was a big first step,” he told me. “They’d never bought a company before…we were just asking to license their data.” The process highlighted the most important playing field upon which the music analytics services compete: getting their hands on every iota of information. The Internet offers myriad ways to share music, and the more of these can be tracked by a label’s A&R department, a management firm, or a corporate brand, the better chance they have of discovering an independent artist who is blowing up on one particular platform.

The other key for each analytics company is the patented formula it uses to compile statistical reports on rising artists and songs. Musicmetric and Next Big Sound present some of their findings in public charts – the latter partners with Billboard to create the Social 50, a measurement of the most active artists on social media, and the Next Big Sound 15, an indicator of artists predicted to go viral based on their current online acceleration – but The Echo Nest keeps its “hotttnesss” rating system hidden, and only paying clients can access each service’s full suite of crunched numbers.

And for good reason: the number crunching produces remarkably accurate predictions of success. For instance, Next Big Sound’s 2015 midyear report showcased how the company’s ability to track YouTube uploads of songs allowed it to predict, last January, that Halsey’s fame would grow exponentially and that Fetty Wap’s “Trap Queen” and OMI’s “Cheerleader” would dominate the summer airwaves. “We’ve been tracking this activity since 2009 online, so we have a lot of patterns for every artist that’s broken in those six years,” said White, “and we can see where they were at this stage in their career and what their trajectory looks like compared to everybody else.”

It seems obvious for music industry professionals and brand partners to consult music analytics regularly, but it also behooves independent artists to use these services as a way to determine where and how their fans are best engaging with their material. In the future, White said, Next Big Sound hopes to convert its data directly into actionable items for delivery to its users instead of merely presenting numbers and leaving the interpretation up to clients.

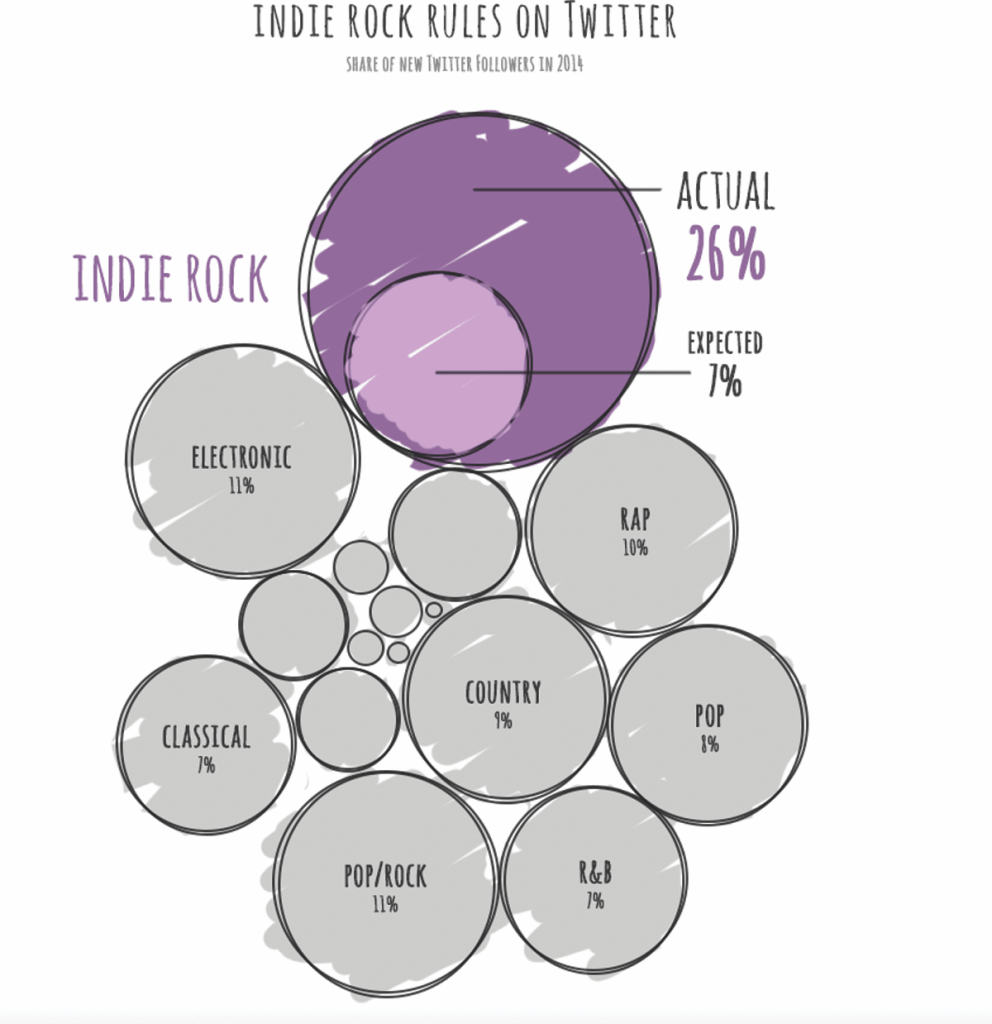

chart originally published at https://www.nextbigsound.com/industryreport/2015summer

An Old Dog’s New Trick: Music Xray

Meanwhile, Mike McCready hasn’t lost hope in analyzing songs themselves. He reconfigured his Hit Song Science to form Music Xray, of which he is the CEO, in 2009. Rather than directing hit predictions at labels and A&R personnel, Music Xray focuses on the artists themselves. For $10, they can put a song through the company’s diagnostics, which combines feedback from five industry professionals and twenty music fans with a patented algorithm to determine the likelihood that the song will be selected for one of the plethora of label opportunities, brand partnerships, or sync deals offered on Music Xray.

“The only purpose of diagnostics is so that upon that first transaction, upon that song coming into our system, we can gather enough information about it to know whether it’s a needle or a strand of hay,” said McCready. “And we can show that information back to the artists.” Doing so ensures that most of the songs submitted to opportunities on Music Xray will be of high quality – with submissions costing an average of $16 and the company’s prediction model based on the assumption that songs are submitted to twenty opportunities, artists whose songs receive low scores will likely leave the site – and thereby turns the service into what McCready describes as an “industry filter,” a place for unsigned talent with high potential to break free of the Internet noise.

Hit Song Science’s original comparison of acoustic properties still has a place on Music Xray in a sort of recommendations role; for example, if a music supervisor uploads “Crazy Train” as a reference track, any artist with a similar sounding track on Music Xray is notified. More interestingly, after six years at the company’s helm and well over a decade in music analytics, McCready is confident enough in his predictions that Music Xray has begun offering to front the submission fees for high-potential songs in exchange for 20% of the resulting deal.

When asked why high-potential artists would give up 20% of a deal they were likely to land anyways, McCready pointed to the investment strategy as a way to finally awaken skeptical musicians to the power of song analysis and prove that Music Xray isn’t just out to nickel-and-dime musicians; once that happens, the company will shift its investments to the industry professionals who bring these artists to market. And McCready is certain it will happen; he likens the music industry’s apprehension to that of mainstream baseball during the advent of “moneyball,” which displaced the same “gut instinct” and artistic “fussiness” that still dominates much of A&R.

It will likely take a string of chart-topping successes uncovered by Music Xray to convince the world at large that analytics should be applied to music itself. Until then, the field’s role in the music industry will be “confined” to collecting and analyzing those trillion data points.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Zach Blumenfeld is a freelance music journalist from Chicago. He will vigorously defend his city’s music scene against any coastal detractors, though that’s probably just his Midwestern inferiority complex acting up. He’s an alumnus of Vanderbilt University, where he hosted a live performance/interview radio show for three years, and now he spends his nights reviewing concerts for Chicago publication Gapers Block. You can follow him on Twitter @zachblumy.

charts courtesy of Next Big Sound.