Really good art is often shaped by the time in which it’s created while also reflecting on how the world it exists in is changing, and if you’re lucky, shaping the discussion of the moment itself.

Thurston Moore’s 7th solo album By the Fire, released September 25th on his own Daydream Library Series label, is now part of this global conversation that we are all having in 2020: the pandemic, personal loss, climate crisis, isolation, anger, frustration, anxiety, uprisings for justice, political unrest, numbness, institutional decay, hopefulness, melancholy, and for some, a little weight gain.

It’s a soundtrack for the time we are meandering through, for all the conversations we are all having. There are no grand calls to action or answers here, nor are there meant to be – this is the music you put on when you think about the world we live in and maybe try to imagine a different one.

By the Fire was recorded earlier in the year in North London and sequenced just before the lockdown. Moore is joined by Deb Googe (My Bloody Valentine) on bass and vocals, James Sedwards on guitar, Jon ‘Wobbly’ Leidecker (Negativland) on electronics, as well as Steve Shelley (Sonic Youth) and Jem Doulton sharing duties on drums.

The album blasts off with “Hashish,” a straight-up rock guitar chugger with classic Moore stacked-note countermelodies that will welcome any Sonic Youth fan right back into the room. Followed by “Cantaloupe,” a druggy, ’60s acid-rock riff featuring lines like, “tiny sun dancing like a raw egg,” and you feel like you’re settling into a grungy album of old, but you’d be wrong.

Here’s where the storyteller, the composer, the poet, the free spirit in Moore takes the reins. In a world of 3:30 minute singles, we’re treated to soundscapes that run 12, 13, even 16:49 minutes long. In an industry that proclaims the album is dead and singles rule, we get 9 songs which feel sewn together with the same thread, comprising 1 hr and 23 minutes of music.

Atmospheric stories like “Sirens” are drenched in sonic discord, with distinct sections of rising tension and release punctuated by a sweet little vocal section at the 9-minute mark. Standouts like “Locomotives” and “Venus” (an instrumental) feel fueled by a sense of chaos and destruction delivered through speedy strumming, overloaded amps, and crashing cymbals. Then there’s the sweet surprise of “Dreamer’s Work,” which no doubt should (will?) be sync’d to a weepy montage of looking back on the main character’s life in a future movie.

It’s not for everyone, a lot of good art isn’t. This isn’t music for jogging, although a few tracks would be great for kickboxing. This is music for people who like to slow down and just listen to music. I know, weird huh?

I was fortunate to chat with Thurston Moore to get his thoughts on this creation, the pandemic, and another surprise project he’s working on.

Performer Mag: How did you accomplish getting an album recorded and released during all of this pandemic madness?

Thurston Moore: Well, I had all these songs together before there was any “so-called” lockdown, you know, a name I don’t really like so much, kind of a prison term. I was just thinking of putting a record out sometime this year, and it probably would have been more towards either the end of the year or just after the New Year. That was the plan. But as soon as I found [us] in “lockdown” and I had all this music, it kind of really just defined how I wanted this record to appear, which is right now. And so that’s what happened. I made a decision to get it sequenced how I wanted and I just sort of put my foot down and said I want this record out, ASAP. Which is, of course, in music industry terms, means many months later.

Interesting that the music matched the moment — did it define which tracks were included or left out?

TM: It definitely defined how I wanted to sequence it and tell a story of this very emotional arc that I felt existed in the narrative of all these songs. So, I sequenced it and packaged it with this title, in complete regards to what was going on. I first started calling this record By the Fire–and it wasn’t the initial intention of the title–but it was at a time when I started seeing there was this anger from so many in the United States and around the world. It’s being fanned, because it definitely is a fire, by the people in charge. So, when I was thinking of names for the album and what it should feel like, I was thinking of fire, the fires being set in the streets. Fire as a cleansing tool where things can rise out of ashes and be renewed with new intelligence, hopefully.

So, the name fit perfectly, but what was the initial origin of naming it By the Fire?

TM: I tell the story about how I saw this image in a film of people sitting around a fire talking about Joe Strummer. It’s called The Future is Unwritten. It’s really good, and there was a device used in it where the filmmaker Julian Temple got all the musicians who used to play with Joe Strummer in a regular rock and roll outfit called the 101ers before he was a full-time punk rocker to share stories about him around a campfire at night, with the flames crackling, and I thought it was really affecting. It was really sweet, and that image stuck with me. It just sort of made me think that, regardless of what happens to us as a society, we will always have to reach out to each other, and see how each other’s thing is. I wanted to talk about how songs are shared around a campfire, much like how Native Americans have passed the story stick around.

Well, now that the stick in your hand, what are you saying?

TM: I was really thinking about the value of communication that is so essential to the human condition. There may be some loners around the planet for what it’s worth, but essentially, I find that people desire company, and need communication to connect to this unity of the species. This unified language of the species, the language of life. And I was just sort of thinking about how that is being challenged to such a degree with a natural born virus that comes out of some kind of mistreatment of the natural world. You know? It attacks only our species and no other species is dealing with it. The animal world doesn’t deal with it, the plant world doesn’t deal with it. It’s just the human species that is getting this attack.

So, I’m exploring how we, as humans, who were being informed to isolate and distance, need to communicate and how it got ramped up to such a degree when this first happened, and everybody reached out to each other through technology. Again, this is our campfire. We’ve been able to develop this technology to the service of saving our sanity.

So many of us haven’t played live in a while and normal touring seems in the distance. Playing live is how so many make a living in this industry, how are you handling it, and what are your plans to get back out on the road?

TM: We played at Rough Trade East for an hour last week, it was the first time they had done it since the pandemic. It was a streamed live concert. I did it with Deb Googe and my drummer, Jem Daulton. We did a really tightened up set. It was rather surreal. We haven’t played together as a group for a couple of months. But it was good, I think. I am planning on doing a short European run in November. The gigs I have booked all have no people or are very socially distanced and safe, streamed regionally. These venues are really hurting, some of the revenue that comes into the gig will go to supporting the life of these venues, and we’ve got to keep these places breathing until we can all sort of get back in the pool.

I have a bit of a hopeful view of us getting through this. Humanity has gotten through so much before. But this is a crisis unlike any other because it is compounded with a climate crisis. I think a lot of what happens in the next few months is really critical to what happens in the next decade.

Your song “L’Ephemere” was included on Bandcamp’s Good Music to Avert the Collapse of American Democracycompilation album in early September 2020 to benefit Stacy Abrams’ organization Fair Fight, which is working for fair elections around the world. This album is coming out right before the U.S. election, it’s in the conversation. What shapes your thinking about the artist’s role in being involved in politics at this moment?

TM: I have a firm belief that anybody who makes art, who makes records, makes music, makes film, makes visual art – if you’re going to have your work, regardless of your discipline, where money or some kind of social exchange is trading hands, it’s essentially, inherently, a political act.

You’re sharing this personal emotion, and that’s a dialogue being made public. It’s political whether you want it to be or not. And so, when I think about putting a record out as a political act, I think, “Well, how can you sort of stand by your own ideology and have a value that is worth sharing with other people?”

And so I think with age, I’m 62 now, I’ve learned that there’s a responsibility that is good to be aware of, and to focus on when releasing work. I never thought about that at all so much when I was in my early 20s and going forward in Sonic Youth. I was just going by the seat of my pants in a way and I didn’t think about the political ramifications of anything. Of course, as Sonic Youth became more mature, we got more politically engaged with some of our songs and some of our interactions with different activism measures. But I never really thought about the group, or the musician, or the actual work, having a political value until sometime later. Especially now, I really do see it, and that was another reason why I wanted this record to come out now, as soon as possible.

Here at Performer we’re kind of gear junkies, what’s your setup to write at home?

TM: I live in a building with a series of flats, so I can’t be too loud. I have this great little Roland Cube, it’s the size of the proto-typical breadbox. It’s a cool little hardcore industrial amp I can fit in a suitcase. I started recording on a little digital Zoom 8-track, which is new to me. I usually like to go to a studio that has an engineer there, I have never liked having the apparatus at home. I like my home to be the library, just to kind of write and read.

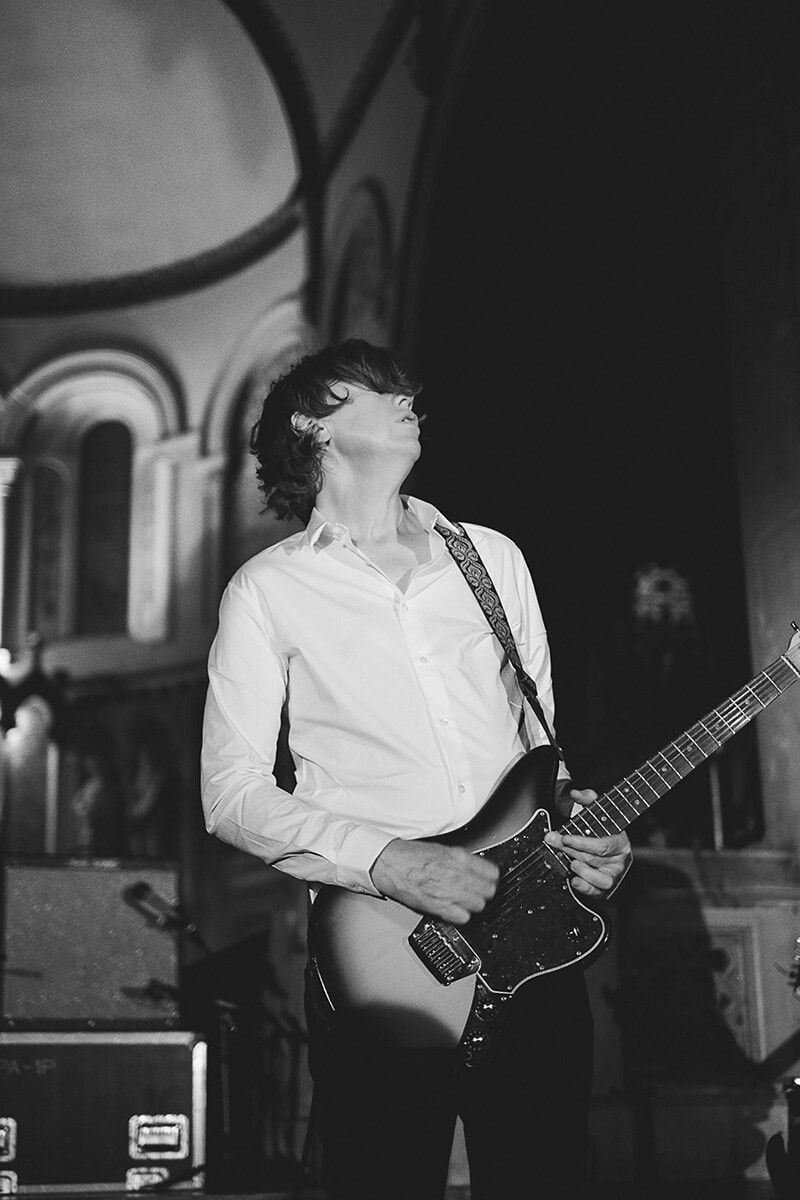

I have an electric Fender 12-string from the late ’60s and a Martin 12-string acoustic. I have my signature Jazzmaster here. It’s not in production anymore, so that’s kind of cool. I have a really early Jazzmaster from ’58-’59. Jazzmasters begin in ’58, which I like, because it was the year I was born. Those are primarily the ones all the time to write on. I use the two different Jazzmasters in two separate tunings. The 12-strings are usually in open tunings, D# to A# to F#.

Have you been writing a lot of new material?

TM: Lately, I have been writing a lot, not just music. Since I’ve had this downtime, I have been able to put down these historical thoughts on paper. I’ve been creating a manuscript about being a musician as a teenager and moving to NYC, and what all these documents meant to me, like the recordings and the literature. Talking at length about that and how those things informed one to get engaged with other people with similar interests and create a band such as what Sonic Youth became.

So, I have this manuscript called “Sonic Life” that I’ll probably publish next year.

Performer readers are independent musicians, and you are somewhat of an indie guru – what are your thoughts on streaming vs digital, and breaking in the business today? What should the “kids” be doing?

TM: When I talk to young musicians, who ask me about these kinds of things, I basically say, you have the privilege of working in two different streams. You have the digital stream, that is completely an open library, and it creates a situation of equal value that’s for all the musicians who work within it. The other stream is like the physical world of actually using your own money to create a vibrational gift item, which is like the record, cassette, CD, book, fanzine, or whatever it is.

With putting music on Bandcamp you have the ability to promote it in any way you want, but your existence is really non-hierarchical; and I found that to be really refreshing. Now, within the physical realm, I always say make something. Because you can’t download an actual record, you can download these songs as content, but you can’t download a vinyl record. Right now, I think we’re kind of in this really cool place, you know, where we can actually sort of still make records, books, and fanzines, etc, and still utilize the online world. Do both. I mean that stylus rubbing across that vinyl groove is something that is only genuine in the physical world, something for people to put in their hands and make that connection.

You can’t roll a joint on a download, you know?

Linkfire for By the Fire all platforms: https://thurstonmoore.lnk.to/ByTheFireWE

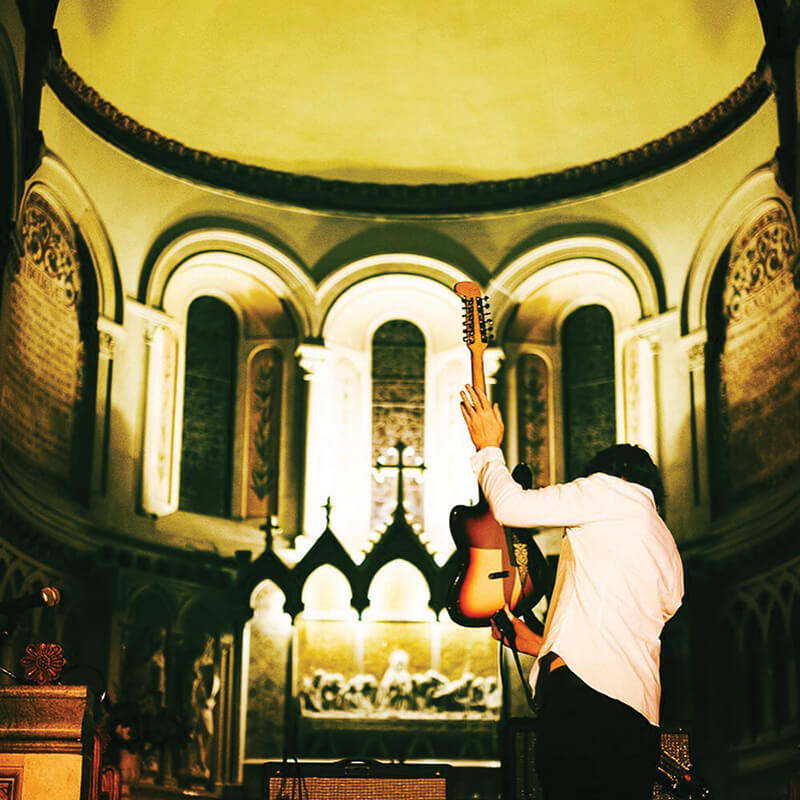

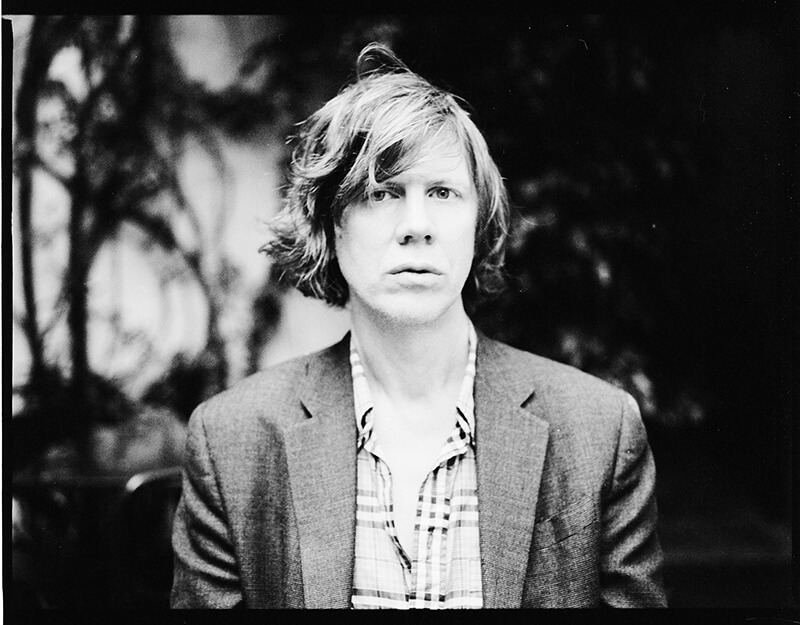

All photos by Photos by Vera Marmelo