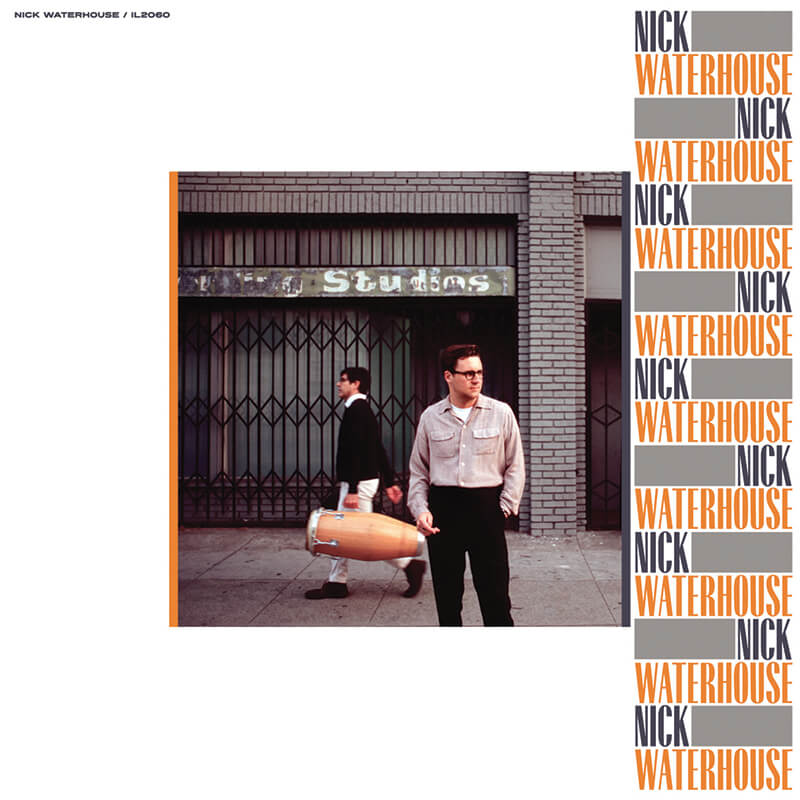

There’s a nostalgic tinge to everything that Nick Waterhouse crafts. As his career traces the California coast, back and forth, he has picked up more warmth and soul between his punchy songwriting, horns and harmony. Growing up in Huntington Beach, spending years in San Francisco and bouncing all around the state in recent years due to social and economic changes in most major cities, his hearty rhythm and blues spirit remains unbroken. Ahead of the March release of his self-titled album with producer Paul Butler (St. Paul and the Broken Bones, Devendra Banhart), Waterhouse took the time to discuss places and frames of mind that he holds close.

Can you describe your experience living in San Francisco?

I left two weeks after graduating high school for San Francisco, went to college there and stayed. I wound up living there for about eight to nine years.

California feels small if you’re a native. My mother’s family lives in central California and doing drives between L.A. and San Francisco with a bunch of my friends was very common. There was a lot of transit when I lived there and my music career really started in both. I was recording in Southern California and playing with a band in San Francisco. By the time the first album came around and I started going on tour, a lot of the scene in San Francisco was changing. There was a lot of money coming into town. It was weird.

When I lived there, it was between the first tech bust in 2001 and the one that we are living in now. It was living in a place that was rapidly pricing out most of the people that I knew and I was tired of the rat race feel, so I moved back to L.A. Around the same time, I went on my first massive campaign for my album. When you are campaigning and touring that much, you don’t really live anywhere. Home is just where your mail goes and where you keep some of your stuff.

Now, I am bouncing around here and there. I didn’t realize that L.A. would accelerate in cost of living in the way that it has.

I have heard that San Francisco in particular, is a totally different city than it was a few years ago, which can be a bit discouraging.

Absolutely. I was just talking to a friend a few weeks ago about a night that I use to DJ at, which played my very first test pressing on a 45, did their final night recently and this is a night that was going for 16 years. The guy running it is a very positive and progressive minded person, so he didn’t have a lot of doom sayings, but it is definitely a question of the changing demographics and this is kind of a direction that everywhere in the world is going. I have seen it just touring. The same thing that is happening in San Francisco is happening in L.A., Austin, Chicago, Pittsburgh, Berlin, just everywhere. That’s just the nature of technology.

What advice do you have for artists in the major cities, who are getting priced out, in keeping music communities alive?

Hmmm, I have been around overzealous, territorial people who conflate community with being active about it and community should be treated like the way that you care about a person. You don’t tell yourself every day that you are supposed to care about something, you just do. It’s more of being an unselfish person who treats others with respect and is also honest with yourself and other people. I think a lot of people get stuck on trying to live in a scene because they are dishonest with themselves about what their core inspirations are. It’s always in hindsight, the way that you perceive a community and I think natural communities will continue among people who are true believers in something together.

It’s about trying to be a better person rather than mak[ing] something. I know a lot of people who wanted to make something, so badly and I was always the one who seemed very unambitious, but now I am making records and most of them are not. You need to be willing to take time, pay your dues and acknowledge other people.

Was there a strong arts community in Huntington Beach when you were growing up?

When I was there, I was so miserable. I felt like there was nothing worthwhile because you want something that is bigger and shinier. It’s that notion that if you read about a scene, you think that it is going to be amazing and would love to be a part of it, but if it is being observed by an outside, it is probably on its way to an end.

It was a very small community with maybe two dozen people, but all of it influenced me. On the other side, being around my dad’s firefighter buddies and the way that they interacted with me, influenced me just as much. All of that swirled in with teenage angst and alienation; it’s always going to feel extra potent.

Physicality seems to be a big part of your musical experience, between playing DJ nights with vinyl and hand-pressing albums. What exactly does the physicality of music mean to you?

The physicality just feels right to me. It’s also something that I am familiar with in that physicality is how I interfaced with music my whole life. I do it with intent, but my intent is ‘this feels right and the other way feels wrong’. It’s a really powerful medium. There are all kinds of ‘up your ass’ descriptions, but it makes you engage with music in a different way.

We are in an era of wellness and being in the moment, and you actually have to be in the moment when you play a record because if you are not paying attention, your hands aren’t working.

How has your relationship with gear changed over time?

All of my equipment is instruments to me. Sometimes they just feel like a tool, but sometimes I can do a new thing with a tool that I have never dealt with before. Since I am seeking my own particular vision, I am always looking to elevate them to something that really excites me.

I got a new RCA microphone preamp before we did this record (‘Nick Waterhouse’) and I didn’t wind up using it as a preamp. We wound up trying it as busing for the entire mix, so the whole record is put through this thing, adding theses pleasant harmonics. The more that I thought about it, the more I thought about how that was essentially how a radio broadcast board was in the ’40s. They (equipment) are all like paints. It’s all different textures, which is something that I’ve always loved.

Follow on Twitter @nickwaterhouse

Photos by Zach Lewis