Between running for office in Athens, performing as Linqua Franqa, helping to unite the city’s burgeoning hip-hop scene and pursuing a doctorate in linguistics, Mariah Parker, only 26, has zero time. It’s also about to get worse since Parker just won that office seat.

It’s impossible to talk about Linqua Franqa, Parker’s musical alter ego, without talking about her history of activism, as well as her background as a teacher and organizer. After moving to Athens, Georgia from a small town outside of Louisville, Kentucky in 2014, Parker became active in both the hip-hop scene and various social activist movements, including anti-discriminations marches, DACA protests and local Women’s Marches. Parker’s passion for activism continued as she founded Hot Corner Hip Hop as “push back against racism and classism in downtown Athens” after venue owners in the downtown area didn’t think hip-hop would bring crowds large enough to make sense financially.

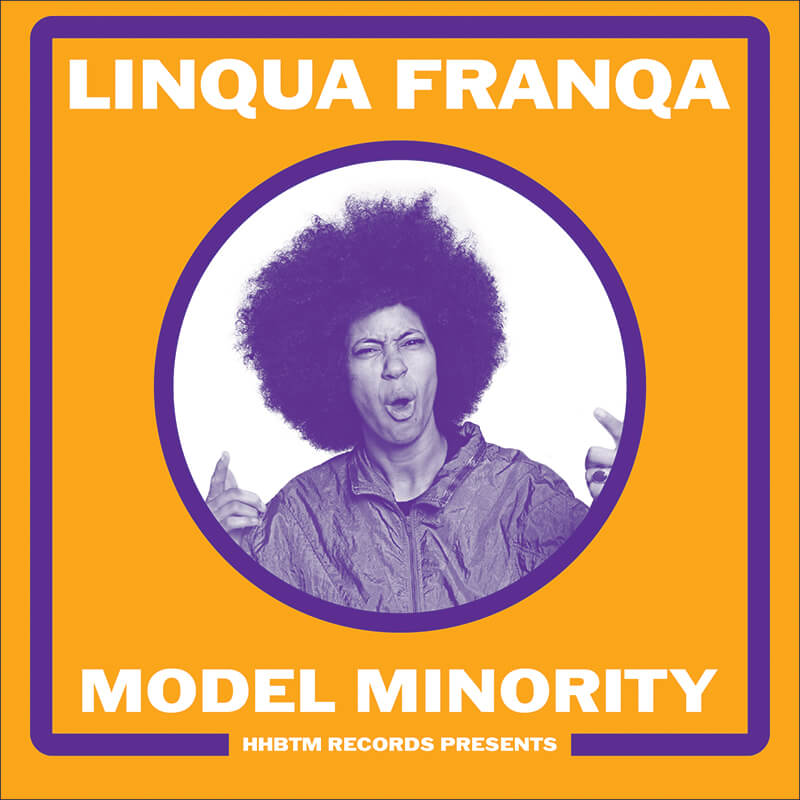

Four years later, Parker’s musical and political lives have blossomed. Her debut full-length as Linqua Franqa (Model Minority, recently re-released on vinyl) earned heaps of local praise for its neo-soul, nineties hip-hop influenced beats and meaningful messages. Franqa’s flow is dense and smooth, boosted by her imaginative use of syntax and storytelling.

In late May, Parker was voted to serve as an Athens-Clarke County commissioner. By June, she was already pushing the University of Georgia to do more to fight poverty and racism. While some may struggle walking the line between politician and performer, Parker embraces it with Linqua Franqa. While Parker was rallying residents to fight for economic stability and racial justice in Athens, Linqua Franqa was doing the same with her music.

The Model Minority LP features tales about addiction, depression, race, politics and feminism. “Might look like Angie Davis if you’re racist, but on closer observation I’m whiter than mayonnaise is,” she raps on “Up Close.”

“Now I don’t trust these summer days ’cause where the fuck were they when I took knife to skin and wanted my entire life to end?” she contemplates on “Eight Weeks.”

We recently sat down with Parker to talk about her new life in politics, her musical career as Linqua Franqa and how she approached writing and recording her debut album.

Before speaking at forums while running for office, one of your closest advisors would often nudge you to “give ’em less Linqua Franqa and more Mariah.”

When Linqua Franqa is on, I can’t turn her off. I feel like Mariah Parker is the person I pretend to be in the daylight so LF can function normally in society.

You’ve said your stage name, Linqua Franqa, is a play on Lingua Franca, a mish mash of dialects. Tell me why you chose it and what it means to you?

Lingua Franca is the linguistic term for a language used to communicate across cultural boundaries. I think hip-hop is a lingua franca, and I want my particular kind of hip-hop to do that as best it can.

Please tell me a bit about where you grew up, how you ended up in Athens and why you’ve stayed there.

I grew up in a small town outside of Louisville. It was flat, white, with little more than a movie theatre and a Walmart to entertain kids. I ended up in Athens after teaching English in Brazil for a year; I briefly moved home, hated it, and while visiting friends in Athens decided to shill out some resumes. I landed a job in a print shop, luckily, and never went back home.

Can you talk about the hip-hop scene in Athens and where you fit into it? Also, please talk a bit about Hot Corner Hip Hop, where it started, what it’s become…

I’m really proud of the hip-hop scene here in Athens. It went from being scattered and lonely three years ago to vibrant, mutually supportive, and challenging in a positive way. I started Hot Corner Hip Hop because I felt lonely here as a hip-hop artist. I wanted to bring folks together who were flung to the far corners of the scene, geographically and socially, by the catapults of racism’s legacy here.

I also had never performed hip-hop, only participated in cyphers and written rhymes, so I wanted to challenge myself to put my work out there by creating a platform where there wasn’t one. HCHH has definitely peaked; I think it’s important to share power and sometimes that means getting out of the way when others have stuff to say, so I’m laying low on that front while others continue to build the movement. But the important work of breaking down racial stigmas and inviting people together across cultural lines has really changed Athens, I think, and I’m still proud of that.

What’s your earliest memory of hearing music that moved you?

My mother is/was a gospel singer, and so the sound of her voice in harmony with her two sisters was intrinsically moving as a child and has influenced the harmonies and R&B stylings of the hooks I write today.

Tell me about recording this album. Where did the beats come from for each song? What was your writing process like for lyrics? Was this your first time in the studio? Was it a challenge?

I wrote the lyrics over a period of about eight years. I’d take them apart, rearrange them, play with the sounds of words, make different meters and rhymes and similes tell different stories, until finally things began to congeal in an arc that I felt happy with, sonically as well as narratively. It was challenging but extremely cathartic also. Yeah, performing these songs over the last two years has been incredibly cathartic. As a result, I’m not afraid or ashamed of what I’ve been through anymore.

When I first started recording, yeah it was my first time in the studio, and you could hear in the recordings that I felt so much unease and was embarrassed by the words coming out of my mouth. After months of recording we eventually threw out everything and started over. Once I’d laid it all out in front of enough crowds, though, I developed the confidence in my stories, in myself despite having lived them, to just own them aloud in the booth. So yes, it was challenging to record but ultimately very rewarding.

Tell us a bit about running for Athens-Clarke County District 2 Commissioner. What’s your history of activism in the community prior to running? What are you hoping to accomplish and why did you choose this specific race?

I see my organizing within the music scene as activism. I’ve also stood up against outright discrimination in bars by agitating alongside local groups like the Athens Anti-Discrimination Movement for a civil rights committee and anti-discrimination ordinance and spoken at rallies for marijuana decriminalize and the abolition of ICE. I chose to run because I felt it was my civic duty; mine was a district where they’d been represented by the same guy for twenty-five years, the kind of guy who never answered phone calls from his constituents, you know the kind. His hand-picked successor was about to run uncontested, too, and I just couldn’t stand for it.

Running seemed like justice, like true democracy. I really want the folks in my neighborhood to be heard and above all else fight for them to have fair wage jobs and good working conditions so that they can provide the kind of lives for their families that everyone deserves. There’s a lot of puzzle pieces to that, but economic liberty is the finished picture.

Tell me about practicing and fully forming your flow. What kind of work did you put in to get where you are. Where does the doctorate in linguistics from University of Georgia fit into all this?

Having studied syntax and phonetics and morphology, I have a neat little analytic toolkit for thinking about how discrete bits of language–syllables, affixes, verb tenses, noun phrases– can recombine, which makes it a lot easier to tell stories in ways that feel nice on your lips, sound lushly dense, and take a few listens to fully unpack. Ideally my dissertation will be in rap form–there are precedents for this already– but we’ll see if I make it all the way through school at all, with everything else going on…

**photos by Stacey Piotrowska